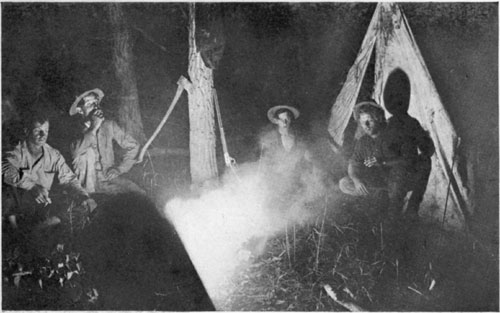

Night in Camp.

Night in Camp.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The River and I, by John G. Neihardt This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The River and I Author: John G. Neihardt Release Date: October 3, 2005 [EBook #16793] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE RIVER AND I *** Produced by Audrey Longhurst, Julia Miller and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's Notes: | Typographical errors and inconsistent spellings found in the original publication have been maintained in this text. Misspelled words are marked, with the correction in the popup. A list of these is found at the end of the book. |

Other Books by

JOHN G. NEIHARDT Indian Tales and Others |

Illustrated

New Edition

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1927

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1910,

By JOHN G. NEIHARDT.

Set up and electrotyped.

Reissued in new format, October, 1927.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

BY THE CORNWALL PRESS

TO

MY MOTHER

The following account of a youthful adventure was written during the winter of 1908, ran as a serial in Putnam's Magazine the following year, and appeared as a book in 1910, five years before "The Song of Hugh Glass," the first piece of my Western Cycle. Many who have cared for my narrative poems, feeling the relation between those and this earlier avowal of an old love, have urged that "The River and I" be reprinted.

J.G.N.

St. Louis, 1927.

IT was Carlyle—was it not?—who said that all great works produce an unpleasant impression on first acquaintance. It is so with the Missouri River. Carlyle was not, I think, speaking of rivers; but he was speaking of masterpieces—and so am I.

It makes little difference to me whether or not an epic goes at a hexameter gallop through the ages, or whether it chooses to be a flood of muddy water, ripping out a channel from the mountains to the sea. It is merely a matter of how the great dynamic force shall express itself.

I have seen trout streams that I thought were better lyrics than I or any of my fellows can ever hope to create. I have heard the moaning of rain winds among mountain pines that struck me as being equal, at least, to Adonais. I have seen the solemn rearing of a mountain peak into the pale dawn that gave me a deep religious appreciation of my significance in the Grand Scheme, as though I had heard and understood a parable from the holy lips of an Avatar. And the vast plains of my native country are as a mystic scroll unrolled, scrawled with a cabalistic writ of infinite things.

In the same sense, I have come to look upon the Missouri as something more than a stream of muddy water. It gave me my first big boy dreams. It was my ocean. I remember well the first time I looked upon my turbulent friend, who has since become as a brother to me. It was from a bluff at Kansas City. I know I must have been a very little boy, for the terror I felt made me reach up to the saving forefinger of my father, lest this insane devil-thing before me should suddenly develop an unreasoning hunger for little boys. My father seemed as tall as Alexander—and quite as courageous. He seemed to fear it almost not at all. And I should have felt little surprise had he taken me in his arms and stepped easily over that mile or so of liquid madness. He talked calmly about it—quite calmly. He explained at what angle one should hold one's body in the current, and how one should conduct one's legs and arms in the whirlpools, providing one should swim across.

Swim across! Why, it took a giant even to talk that way! For the summer had smitten the distant mountains, and the June floods ran. Far across the yellow swirl that spread out into the wooded bottom-lands, we watched the demolition of a little town. The siege had reached the proper stage for a sally, and the attacking forces were howling over the walls. The sacking was in progress. Shacks, stores, outhouses suddenly developed a frantic desire to go to St. Louis. It was a weird retreat in very bad order. A cottage with a garret window that glared like the eye of a Cyclops, trembled, rocked with the athletic lift of the flood, made a panicky plunge into a convenient tree; groaned, dodged, and took off through the brush like a scared cottontail. I felt a boy's pity and sympathy for those houses that got up and took to their legs across the yellow waste. It did not seem fair. I have since experienced the same feeling for a jack-rabbit with the hounds a-yelp at its heels.

But—to swim this thing! To fight this cruel, invulnerable, resistless giant that went roaring down the world with a huge uprooted oak tree in its mouth for a toothpick! This yellow, sinuous beast with hell-broth slavering from its jaws! This dare-devil boy-god that sauntered along with a town in its pocket, and a steepled church under its arm for a moment's toy! Swim this?

For days I marvelled at the magnificence of being a fullgrown man, unafraid of big rivers.

But the first sight of the Missouri River was not enough for me. There was a dreadful fascination about it—the fascination of all huge and irresistible things. I had caught my first wee glimpse into the infinite; I was six years old.

Many a lazy Sunday stroll took us back to the river; and little by little the dread became less, and the wonder grew—and a little love crept in. In my boy heart I condoned its treachery and its giant sins. For, after all, it sinned through excess of strength, not through weakness. And that is the eternal way of virile things. We watched the steamboats loading for what seemed to me far distant ports. (How the world shrinks!) A double stream of "roosters" coming and going at a dog-trot rushed the freight aboard; and at the foot of the gang-plank the mate swore masterfully while the perspiration dripped from the point of his nose.

And then—the raucous whistles blew. They reminded me of the lions roaring at the circus. The gang-plank went up, the hawsers went in. The snub nose of the steamer swung out with a quiet majesty. Now she feels the urge of the flood, and yields herself to it, already dwindled to half her size. The pilot turns his wheel—he looks very big and quiet and masterful up there. The boat veers round; bells jangle. And now the engine wakens in earnest. She breathes with spurts of vapor!

Breathed? No, it was sighing; for about it all clung an inexplicable sadness for me—the sadness that clings about all strong and beautiful things that must leave their moorings and go very, very far away. (I have since heard it said that river boats are not beautiful!) My throat felt as though it had smoke in it. I felt that this queenly thing really wanted to stay; for far down the muddy swirl where she dwindled, dwindled, I heard her sobbing hoarsely.

Off on the perilous flood for "faërie lands forlorn"! It made the world seem almost empty and very lonesome.

And then the dog-days came, and I saw my river tawny, sinewy, gaunt—a half-starved lion. The long dry bars were like the protruding ribs of the beast when the prey is scarce, and the ropy main current was like the lean, terrible muscles of its back.

In the spring it had roared; now it only purred. But all the while I felt in it a dreadful economy of force, just as I have since felt it in the presence of a great lean jungle-cat at the zoo. Here was a thing that crouched and purred—a mewing but terrific thing. Give it an obstacle to overcome—fling it something to devour; and lo! the crushing impact of its leap!

And then again I saw it lying very quietly in the clutch of a bitter winter—an awful hush upon it, and the white cerement of the snow flung across its face. And yet, this did not seem like death; for still one felt in it the subtle influence of a tremendous personality. It slept, but sleeping it was still a giant. It seemed that at any moment the sleeper might turn over, toss the white cover aside and, yawning, saunter down the valley with its thunderous seven-league boots. And still, back and forth across this heavy sleeper went the pigmy wagons of the farmers taking corn to market!

But one day in March the far-flung arrows of the geese went over. Honk! honk! A vague, prophetic sense crept into the world out of nowhere—part sound, part scent, and yet too vague for either. Sap seeped from the maples. Weird mist-things went moaning through the night. And then, for the first time, I saw my big brother win a fight!

For days, strange premonitory noises had run across the shivering surface of the ice. Through the foggy nights, a muffled intermittent booming went on under the wild scurrying stars. Now and then a staccato crackling ran up the icy reaches of the river, like the sequent bickering of Krags down a firing line. Long seams opened in the disturbed surface, and from them came a harsh sibilance as of a line of cavalry unsheathing sabres.

But all the while, no show of violence—only the awful quietness with deluge potential in it. The lion was crouching for the leap.

Then one day under the warm sun a booming as of distant big guns began. Faster and louder came the dull shaking thunders, and passed swiftly up and down, drawling into the distance. Fissures yawned, and the sound of the grumbling black water beneath came up. Here and there the surface lifted—bent—broke with shriekings, groanings, thunderings. And then——

The giant turned over, yawned and got to his feet, flinging his arms about him! Barriers formed before him. Confidently he set his massive shoulders against them—smashed them into little blocks, and went on singing, shouting, toward the sea. It was a glorious victory. It made me very proud of my big brother. And yet all the while I dreaded him—just as I dread the caged tiger that I long to caress because he is so strong and so beautiful.

Since then I have changed somewhat, though I am hardly as tall, and certainly not so courageous as Alexander. But I have felt the sinews of the old yellow giant tighen about my naked body. I have been bent upon his hip. I have presumed to throw against his Titan strength the craft of man. I have often swum in what seemed liquid madness to my boyhood. And we have become acquainted through battle. No friends like fair foes reconciled!

And I have been panting on his bars, while all about me went the lisping laughter of my brother. For he has the strength of a god, the headlong temper of a comet; but along with these he has the glad, mad, irresponsible spirit of a boy. Thus ever are the epic things.

The Missouri is unique among rivers. I think God wished to teach the beauty of a virile soul fighting its way toward peace—and His precept was the Missouri. To me, the Amazon is a basking alligator; the Tiber is a dream of dead glory; the Rhine is a fantastic fairy-tale; the Nile a mummy, periodically resurrected; the Mississippi, a convenient geographical boundary line; the Hudson, an epicurean philosopher.

But the Missouri—my brother—is the eternal Fighting Man!

I love things that yearn toward far seas: the singing Tennysonian brooks that flow by "Philip's farm" but "go on forever"; the little Ik Walton rivers, where one may "study to be quiet and go a-fishing"! The Babylonian streams by which we have all pined in captivity; the sentimental Danube's which we can never forget because of "that night in June"; and at a very early age I had already developed a decent respect for the verbose manner in which the "waters come down at Lodore."

But the Missouri is more than a sentiment—even more than an epic. It is the symbol of my own soul, which is, I surmise, not unlike other souls. In it I see flung before me all the stern world-old struggle become materialized. Here is the concrete representation of the earnest desire, the momentarily frustrate purpose, the beating at the bars, the breathless fighting of the half-whipped but never-to-be-conquered spirit, the sobbing of the wind-broken runner, the anger, the madness, the laughter. And in it all the unwearying urge of a purpose, the unswerving belief in the peace of a far away ocean.

If in a moment of despair I should reel for a breathing space away from the fight, with no heart for battle-cries, and with only a desire to pray, I could do it in no better manner than to lift my arms above the river and cry out into the big spaces: "You who somehow understand—behold this river! It expresses what is voiceless in me. It prays for me!"

Not only in its physical aspect does the Missouri appeal to the imagination. From Three Forks to its mouth—a distance of three thousand miles—this zigzag watercourse is haunted with great memories. Perhaps never before in the history of the world has a river been the thoroughfare of a movement so tremendously epic in its human appeal, so vastly significant in its relation to the development of man. And in the building of the continent Nature fashioned well the scenery for the great human story that was to be enacted here in the fullness of years. She built her stage on a large scale, taking no account of miles; for the coming actors were to be big men, mighty travelers, intrepid fighters, laughers at time and space. Plains limited only by the rim of sky; mountains severe, huge, tragic as fate; deserts for the trying of strong spirits; grotesque volcanic lands—dead, utterly ultra-human—where athletic souls might struggle with despair; impetuous streams with their rapids terrible as Scylla, where men might go down fighting: thus Nature built the stage and set the scenes. And that the arrangements might be complete, she left a vast tract unfinished, where still the building of the world goes on—a place of awe in which to feel the mighty Doer of Things at work. Indeed, a setting vast and weird enough for the coming epic. And as the essence of all story is struggle, tribes of wild fighting men grew up in the land to oppose the coming masters; and over the limitless wastes swept the blizzards.

I remember when I first read the words of Vergil beginning Ubi tot Simois, "where the Simois rolls along so many shields and helmets and strong bodies of brave men snatched beneath its floods." The far-seeing sadness of the lines thrilled me; for it was not of the little stream of the Æneid that I thought while the Latin professor quizzed me as to constructions, but of that great river of my own epic country—the Missouri. Was I unfair to old Vergil, think you? As for me, I think I flattered him a bit! And in this modern application, the ancient lines ring true. For the Missouri from Great Falls to its mouth is one long grave of men and boats. And such men!

It is a time-honored habit to look back through the ages for the epic things. Modern affairs seem a bit commonplace to some of us. A horde of semi-savages tears down a town in order to avenge the theft of a faithless wife who was probably no better than she should have been—and we have the Iliad. A petty king sets sail for his native land, somehow losing himself ten years among the isles of Greece—and we have the Odyssey. (I would back a Missouri River "rat" to make the distance in a row boat within a few months!) An Argive captain returns home after an absence of ten years to find his wife interested overmuch in a friend who went not forth to battle; a wrangle ensues; the tender spouse finishes her lord with an axe—and you have the Agamemnon. (To-day we should merely have a sensational trial, and hysterical scareheads in the newspapers.) Such were the ancient stories that move us all—sordid enough, be sure, when you push them hard for fact. But time and genius have glorified them. Not the deeds, but Homer and Æschylus and the hallowing years are great.

We no longer write epics—we live them. To create an epic, it has been said somewhere, the poet must write with the belief that the immortal gods are looking over his shoulder.

We no longer prostrate ourselves before the immortal gods. We have long since discovered the divinity within ourselves, and so we have flung across the continents and the seas the visible epics of will.

The history of the American fur trade alone makes the Trojan War look like a Punch and Judy show! and the Missouri River was the path of the conquerors. We have the facts—but we have not Homer.

An epic story in its essence is the story of heroic men battling, aided or frustrated by the superhuman. And in the fur trade era there was no dearth of battling men, and the elements left no lack of superhuman obstacles.

I am more thrilled by the history of the Lewis and Clark expedition than by the tale of Jason. John Colter, wandering three years in the wilderness and discovering the Yellowstone Park, is infinitely more heroic to me that Theseus. Alexander Harvey makes Æneas look like a degenerate. It was Harvey, you know, who fell out with the powers at Fort Union, with the result that he was ordered to report at the American Fur Company's office at St. Louis before he could be reinstated in the service. This was at Christmas time—Christmas of a Western winter. The distance was seventeen hundred miles, as the crow flies. "Give me a dog to carry my blankets," said he, "and by God I'll report before the ice goes out!" He started afoot through the hostile tribes and blizzards. He reported at St. Louis early in March, returning to Union by the first boat out that year. And when he arrived at the Fort, he called out the man who was responsible for the trouble, and quietly killed him. That is the stern human stuff with which you build realms. What could not Homer do with such a man? And when one follows him through his recorded career, even Achilles seems a bit ladylike beside him!

The killing of Carpenter by his treacherous friend, Mike Fink, would easily make a whole book of hexameters—with a nice assortment of gods and goddesses thrown in. There was a woman in the case—a half-breed. Well, this half-breed woman fascinates me quite as much as she whose face "launched a thousand ships and burnt the topless towers of Ilium"! In ancient times the immortal gods scourged nations for impieties; and, as we read, we feel the black shadow of inexorable fate moving through the terrific gloom of things. But the smallpox scourge that broke out at Fort Union in 1837, sweeping with desolation through the prairie tribes, moves me more than the storied catastrophes of old. It was a Reign of Terror. Even Larpenteur's bald statement of it fills me with the fine old Greek sense of fate. Men sickened at dawn and were dead at sunset. Every day a cartload or two of corpses went over the bluff into the river; and men became reckless. Larpenteur and his friend joked daily about the carting of the gruesome freight. They felt the irresistible, and they laughed at it, since struggle was out of the question. Some drank deeply and indulged in hysterical orgies. Some hollowed out their own graves and waited patiently beside them for the hidden hand to strike. At least fifteen thousand died—Audubon says one hundred and fifty thousand; and the buffalo increased rapidly—because the hunters were few.

Would not such a story—here briefly sketched—move old Sophocles?

The story of the half-breed woman—a giantess—who had a dozen sons, has about it for me all the glamour of an ancient yarn. The sons were free-trappers, you know, and, incidentally, thieves and murderers. (I suspect some of our classic heroes were as much!) But they were doubtless living up to the light that was in them, and they were game to the finish. So was the old woman; they called her "the mother of the devils." Trappers from the various posts organized to hunt them down, and the mother and the sons barricaded their home. The fight was a hard one. One by one the "devils" fell fighting about their mother. And then the besieging party fired the house. With all her sons wounded or dead, the old woman sallied forth. She fought like a grizzly and went down like a heroine.

A sordid, brutal story? Ah, but it was life! Fling about this story of savage mother-love the glamour of time and genius, and it will move you!

And the story of old Hugh Glass! Is it not fateful enough to be the foundation of a tremendous Æschylean drama? A big man he was—old and bearded. A devil to fight, a giant to endure, and an angel to forgive! He was in the Leavenworth campaign against the Aricaras, and afterward he went as a hunter with the Henry expedition. He had a friend—a mere boy—and these two were very close. One day Glass, who was in advance of the party, beating up the country for game, fell in with a grizzly; and when the main party came up, he lay horribly mangled with the bear standing over him. They killed the bear, but the old man seemed done for; his face had all the features scraped off, and one of his legs went wabbly when they lifted him.

It was merely a matter of one more man being dead, so the expedition pushed on, leaving the young friend with several others to see the old man under ground. But the old man was a fighter and refused to die, though he was unconscious: held on stubbornly for several days, but it seemed plain enough that he would have to let go soon. So the young friend and the others left the old man in the wilderness to finish up the job by himself. They took his weapons and hastened after the main party, for the country was hostile.

But one day old Glass woke up and got one of his eyes open. And when he saw how things stood, he swore to God he would live, merely for the sake of killing his false friend. He crawled to a spring near by, where he found a bush of ripe bull-berries. He waited day after day for strength, and finally started out to crawl a small matter of one hundred miles to the nearest fort. And he did it, too! Also he found his friend after much wandering—and forgave him.

Fancy Æschylus working up that story with the Furies for a chorus and Nemesis appearing at intervals to nerve the old hero!

And Rose the Renegade, who became the chief of a powerful tribe of Indians! And Father de Smet, one of the noblest figures in history, carrying the gospel into the wilderness! And Le Barge, the famous pilot, whose biography reads like a romance! In the history of the Missouri River there were hundreds of these heroes, these builders of the epic West. Some of them were violent at times; some were good men and some were bad. But they were masterful always. They met obstacles and overcame them. They struck their foes in front. They thirsted in deserts, hungered in the wilderness, froze in the blizzards, died with the plagues, and were massacred by the savages. Yet they conquered. Heroes of an unwritten epic! And their pathway to defeat and victory was the Missouri River.

If you wish to have your epic spiced with the glamour of kings, the history of the river will not fail you; for in those days there were kings as well as giants in the land. Though it was not called such, all the blank space of the map of the Missouri River country and even to the Pacific, was one vast empire—the empire of the American Fur Company; and J.J. Astor in New York spoke the words that filled the wilderness with deeds. Thus democratic America once beheld within her own confines the paradox of an empire truly Roman in character.

Here and there on the banks of the great waterway—an imperial road that would have delighted Cæsar—many forts were built. These were the ganglia of that tremendous organism of which Astor was the brain. The bourgeois of one of these posts was virtually proconsul with absolute power in his territory. Mackenzie at Union—which might be called the capital of the Upper Missouri country—was called "King of the Missouri." He had an eye for seeing purple. At one time he ordered a complete suit of armor from England; and even went so far as to have medals struck, in true imperial fashion, to be distributed among his loyal followers.

Far and wide these Western American kings flung the trappers, their subjects, into the wilderness. Verily, in the unwritten "Missouriad" there is no lack of regal glamour.

The ancients had a way of making vast things small enough to be familiar. They make gods of the elements, and natural phenomena became to them the awful acts of the gods.

These moderns made no gods of the elements—they merely conquered them! The ancients idealized the material. These moderns materialized the ideal. The latter method is much more appealing to me—an American—than the former. I love the ancient stories; but it is for the modern marvellous facts that I reserve my admiration.

When one looks upon his own country as from a height of years, old tales lose something of their wonder for him. It is owing to this attitude that the prospect of descending the great river in a power canoe from the head of navigation gave me delight.

Days and nights filled with the singing and muttering of my big brother! And I would need only to close my eyes, and all about me would come and go the ghosts of the mighty doers—who are my kin. Big men, bearded and powerful, pushing up stream with the cordelle on their shoulders! Voyageurs chanting at the paddles! Mackinaws descending with precious freights of furs! Steamboats grunting and snoring up stream! Old forts sprung up again out of the dusk of things forgotten, with all the old turbulent life, where in reality to-day the plough of the farmer goes or the steers browse! Forgotten battles blowing by in the wind! And from a bluff's summit, here and there, ghostly war parties peering down upon me—the lesser kin of their old enemies—taking a summer's outing where of old went forth the fighting men, the builders of the unwritten epic!

OUR party of three left the railroad at Great Falls, a good two-days' walk up river from Benton, the head of Missouri River navigation, to which point our boat material had been shipped and our baggage checked.

A vast sun-burned waste of buffalo-grass, prickly pears, and sagebrush stretched before us to the north and east; and on the west the filmy blue contour of the Highwoods Mountains lifted like sun-smitten thunder clouds in the July swelter. One squinting far look, however, told you that these were not rain clouds. The very thought of rain came to you with the vagueness of some birth-surviving memory of a former time. You looked far up and out to the westward and caught the glint of snow on the higher peaks. But the sight was unconvincing; it was like a story told without the "vital impulse." Always had these plains blistered under this July sun; always had the spots of alkali made the only whiteness; and the dry harsh snarl and snap of the grasshoppers' wings had pricked this torrid silence through all eternity.

A stern and pitiless prospect for the amateur pedestrian, to be sure; for devotees of the staff and pack have come to associate pedestrianism with the idyllic, and the idyllic nourishes only in a land of frequent showers. Theocritus and prickly pears are not compatible. Yet it was not without a certain thrill of exaltation that we strapped on our packs and stretched our legs after four days on the dusty plush.

And though ahead of us lay no shady, amiably crooked country roads and bosky dells, wherein one might lounge and dawdle over Hazlitt, yet we knew how crisscross cattle-trails should take us skirting down the river's sixteen miles of awe.

Five hundred miles below its source, the falls of the Missouri begin with a vertical plunge of sixty feet. This is the Black Eagle Falls, presumably named so by Lewis and Clark and other explorers, because of the black eagles found there.

With all due courtesy to my big surly grumbling friend, the Black Eagle Falls, I must say that I was a bit disappointed in him. Oh! he is quite magnificent enough, and every inch a Titan, to be sure; but of late years it seems he has taken up with company rather beneath him. First of all, he has gone to work in a most plebeian, almost slave-like fashion, turning wheels and making lights and dragging silly little trolley cars about a straggling town. Also, he hobnobs continually with a sprawling, brawling, bad-breathed smelter, as no respectable Titan should do. And on top of it all—and this was the straw that broke the back of my sentimental camel—he allows them to maintain a park on the cliffs above him, where the merest white-skinned, counter-jumping pigmy may come of a Sunday for his glass of pop and a careless squint at the toiling Titan. Puny Philistines eating peanuts and watching Samson at his Gaza stunt! I like it not. Rather would I see the Muse Clio pealing potatoes or Persephone busy with a banana cart! Encleadus wriggling under a mountain is well enough; but Enceladus composedly turning a crank for little men—he seemed too heavy for that light work.

Leaning on the frame observation platform, I closed my eyes, and in the dull roar that seemed the voices of countless ages, the park and the smelter and the silly bustling trolley cars and the ginger-ale and the peanuts and my physical self—all but my own soul—were swallowed up. I saw my Titan brother as he was made—four hundred yards of writhing, liquid sinew, strenuously idle, magnificently worthless, flinging meaningless thunders over the vast arid plain, splendidly empty under sun and stars! I saw him as La Verendrye must have seen him—busy only at the divine business of being a giant. And for a moment behind shut eyes, it seemed very inconsequential to me that cranks should be turned and that trolley cars should run up and down precisely in the same place, never getting anywhere, and that there should be anything in all that tract but an austere black eagle or two, and my own soul, and my Titan brother.

When I looked again, I could half imagine the old turbulent fellow winking slyly at me and saying in that undertone you hear when you forget the thunders for a moment: "Don't you worry about me, little man. It's all a joke, and I don't mind. Only to-morrow and then another to-morrow, and there won't be any smelters or trolley cars or ginger-ale or peanuts or sentimentalizing outers like yourself. But I'll be here howling under sun and stars."

Whereupon I posed the toiling philosopher before the camera, pressed the bulb, and descended from the summit of the cliff (as well as from my point of view) to the trail skirting northward up the river, leaving Encleadus grumbling at his crank.

Perhaps, after all, cranks really have to be turned. Still, it seems too bad, and I have long bewailed it almost as a personal grief, that utility and ugliness should so often be running mates.

They tell me that the Matterhorn never did a tap of work; and you couldn't color one Easter egg with all the gorgeous sunsets of the world! May we all become, some day, perfectly useless and beautiful!

At the foot of the first fall, a mammoth spring wells up out of the rock. Nobody tells you about it; you run across it by chance, and it interests you much more in that way. It would seem that a spring throwing out a stream equivalent to a river one hundred yards wide and two feet deep would deserve a little exploitation. Down East they would have a great white sprawling hotel built close by it wherein one could drink spring water (at a quarter the quart), with half a pathology pasted on the bottle as a label. But nobody seems to care much about so small an ooze out there: everything else is so big. And so it has nothing at all to do but go right on being one of the very biggest springs of all the world. This is really something; and I like it better than the quarter-per-quart idea.

In sixteen miles the Missouri River falls four hundred feet. Incidentally, this stretch of river is said to be capable of producing the most tremendous water-power in the world.

After skirting four miles of water that ran like a mill-race, we came upon the Rainbow Falls, where a thousand feet of river takes a drop of fifty feet over a precipice regular as a wall of masonry. This was much more to my liking—a million horse-power or so busy making rainbows! Bully!

It was a very hot day and the sun was now high. I sat down to wipe the sweat out of my eyes. I wished to get acquainted with this weaver of iridescent nothings who knew so well the divine art of doing nothing at all and doing it good and hard! After all, it isn't so easy to do nothing and make it count!

And in the end, when all broken lights have blended again with the Source Light, I'm not so sure that rainbows will seem less important than rows and rows of arc lights and clusters and clusters of incandescent globes. Are you? I can contract an indefinable sort of heartache from the blue sputter of a city light that snuffs out moon and stars for tired scurrying folks: but the opalescent mist-drift of the Rainbow Falls wove heavens for me in its sheen, and through its whirlwind rifts and crystal flaws, far reaches opened up with all the heart's desire at the other end. You shut your eyes with that thunder in your ears and that gusty mist on your face, and you see it very plainly—more plainly than ever so many arc lights could make you see it—the ultimate meaning of things. To be sure, when you open your eyes again, it's all gone—the storm-flung rainbows seem to hide it again.

A mile below, we came upon the Crooked Falls of twenty feet. Leaving the left bank and running almost parallel with it for some three hundred yards, then turning and making a horseshoe, and returning to the right bank almost opposite the place of first observation, this fall is nearly a mile in length, being an unbroken sheet for that distance. This one, also, does nothing at all, and in a beautifully irregular way. Somehow it made me think of Walt Whitman! But we left it soon, swinging out into the open parched country. We knew all this turbulence to be merely the river's bow before the great stunt.

As we swung along, kicking up the acrid alkali dust from the cattle-trail that snaked its way through the cactus and sagebrush, the roar behind us died; and before us, far away, dull muffled thunders grew up in the hush of the burning noon. Thunders in a desert, and no cloud! For an hour we swung along the trail, and ever the thunders increased—like the undertone of the surf when the sea whitens. We were approaching the Great Falls of the Missouri. There were no sign posts in that lonesome tract; no one of whom to ask the way. Little did we need direction. The voice of thunder crying in the desert led us surely.

A half-hour more of clambering over shale-strewn gullies, up sun-baked watercourses, and we found ourselves toiling up the ragged slope of a bluff; and soon we stood upon a rocky ledge with the thunders beneath us. Damp gusts beat upward over the blistering scarp of the cliff. I lay down, and crawling to the edge, looked over. Two hundred feet below me—straight down as a pebble drops—a watery Inferno raged, and far-flung whirlwinds all but exhausted with the dizzy upward reach, whisked cool, invisible mops of mist across my face.

Flung down a preliminary mile of steep descent, choked in between soaring walls of rock four hundred yards apart, innumerable crystal tons rushed down ninety feet in one magnificent plunge. You saw the long bent crest—shimmering with the changing colors of a peacock's back—smooth as a lake when all winds sleep; and then the mighty river was snuffed out in gulfs of angry gray. Capricious river draughts, sucking up the damp defile, whipped upward into the blistering sunlight gray spiral towers that leaped into opal fires and dissolved in showers of diamond and pearl and amethyst.

I caught myself tightly gripping the ledge and shrinking with a shuddering instinctive fear. Then suddenly the thunders seemed to stifle all memory of sound—and left only the silent universe with myself and this terribly beautiful thing in the midst of utter emptiness. And I loved it with a strange, desperate, tigerish love. It expressed itself so magnificently; and that is really all a man, or a waterfall, or a mountain, or a flower, or a grasshopper, or a meadow lark, or an ocean, or a thunderstorm has to do in this world. And it was doing it right out in the middle of a desert, bleak, sun-leprosied, forbidding, with only the stars and the moon and the sun and a cliff-swallow or two to behold. Thundering out its message into the waste places, careless of audiences—like a Master! Bully, grizzled old Master-Bard singing—as most of them do—to empty benches! And it had been doing that ten thousand thousand years, and would do so for ten thousand thousand more, and never pause for plaudits. I suspect the soul of old Homer did that—and is still doing it, somehow, somewhere. After all there isn't much difference between really tremendous things—Homer or waterfalls or thunderstorms—is there? It's only a matter of how things happen to be big.

I was absent-mindedly chasing some big thundering line of Sophocles when Bill, the little Cornishman, ran in between me and the evasive line: "Lord! what a waste of power!"

There is some difference in temperaments. Most men, I fancy, would have enjoyed a talk with a civil engineer upon that ledge. I should have liked to have Shelley there, myself! It's the difference between poetry and horse-power, dithyrambics and dynamos, Keats and Kipling! What is the energy exerted by the Great Falls of the Missouri? How many horse-power did Shelley fling into the creation of his West Wind? How many foot-pounds did the boy heart of Chatterton beat before it broke? Something may be left to the imagination!

We backtrailed to a point where the cliff fell away into a rock-strewn incline, and clambered down a break-neck slope to the edge of the crystal broil. There was a strange exhilaration about it—a novel sense of discovering a natural wonder for ourselves. We seemed the first men who had ever been there: that was the most gripping thing about it.

Aloof, stupendous, terriffic, staggering in the intensity of its wild beauty, you reach it by a trail. There are no 'busses running and you can't buy a sandwich or a peanut or a glass of beer within ten miles of its far-flung thunders. For twentieth century America, that is doing rather well!

Skirting the slippery rocks at the lip of the mad flood, we swung ourselves about a ledge, dripping with the cool mist-drift; descended to the level of the lower basin, where a soaking fog made us shiver; pushed through a dripping, oozing, autumnal sort of twilight, and came out again into the beat of the desert sun, to look squarely into the face of the giant.

A hawk wheeled and swooped and floated far up in the dazzling air. Somehow that hawk seemed to make the lonely place doubly lonely. Did you ever notice how a lone coyote on a snow-heaped prairie gives you a heartache, whereas the empty waste would only have exhilarated you? Always, it seemed, that veering hawk had hung there, and would hang so always—outliving the rising of suns and the drifting of stars and the visits of the moon.

A vague sense of grief came over me at the thought of all this eternal restlessness, this turbulent fixity; and, after all, it seemed much greater to be even a very little man, living largely, dying, somehow, into something big and new; than to be this Promethean sort of thing, a giant waterfall in a waste.

I have known men who felt dwarfed in the presence of vast and awful things. I never felt bigger than when I first looked upon the ocean. The skyward lift of a mountain peak makes me feel very, very tall. And when a thunderstorm comes down upon the world out of the northwest, with jagged blades of fire ripping up the black bellies of the clouds, I know all about the heart of Attila and the Vikings and tigers and Alexander the Great! So I think I grew a bit out there talking to that water-giant who does nothing at all—not even a vaudeville stunt—and does it so masterfully.

By and by they'll build a hotel in the flat at the edge of the lower basin; plant prim flowers in very prim beds; and rob you on the genteel European plan. Comfortably sitting in a willow chair on the broad veranda, one will read the signs on those cliffs—all about the best shoes to wear, and what particular pill of all the pills that be, should be taken for that ailing kidney. But it will not be I who shall sit in that willow chair on that broad, as yet unbuilt, veranda.

The sun was glinting at the rim of the cliffs, and the place of awe and thunders was slowly filling with shadow. We found a steep trail, inaccessible for vehicles, leading upward in the direction of Benton. It was getting that time of day when even a sentimentalist wants a beefsteak, especially if he has hiked over dusty scorching trails and scrambled over rocks all day.

Some kind man back in the town, with a fund of that most useless article, information, had told us of a place called Goodale, theoretically existing on the Great Northern Railroad between Great Falls and Benton. We had provided only for luncheon, trusting to fate and Goodale for supper.

Goodale! A truly beautiful name! No doubt in some miraculous way the character of the country changed suddenly just before you got there merely to justify the name. Surely no one would have the temerity to conjure up so beautiful a name for a desert town. Yet, half unwillingly, I thought of a little place I once visited—against my will, since the brakeman put me off there—by the name of Forest City. I remembered with misgivings how there wasn't a tree within something like four hundred miles. But I pushed that memory aside as a lying prophet. I believed in Goodale and beefsteak. Goodale would be a neat, quiet little town, set snugly in a verdant valley. We would come into it by starlight—down a careless gypsying sort of country road; and there would be the sound of a dear little trickling bickering cool stream out in the shadows of the trees fringing the approach to Goodale. And we'd pass pretty little cottages with vines growing over the doors, and hollyhocks peeping over the fences, and cheerful lights in the windows.

Goodale! And then, right in the middle of the town (no, village—the word is cosier somehow)—right in the middle of the village there would be a big restaurant, with such alluring scents of beefsteak all about it.

I set the pace up that trail. It was a swinging, loose, cavalry-horse sort of pace—the kind that rubs the blue off the distance and paints the back trail gray. Goodale was a sort of Mecca. I thought of it with something like a religious awe. How far was Goodale, would you suppose? Not far, certainly, once we found the railroad.

We made the last steep climb breathlessly, and came out on the level. A great, monotonous, heartachy prairie lay before us—utterly featureless in the twilight. Far off across the scabby land a thin black line swept out of the dusk into the dusk—straight as a crow's flight. It was the railroad. We made a cross-cut for it, tumbling over gopher holes, plunging through sagebrush, scrambling over gullies that told the incredible tale of torrents having been there once. I ate quantities of alkali dust and went on believing in Goodale and beefsteak. Beefsteak became one of the principal stations on the Great Northern Railroad, so far as I was concerned personally. That is what you might call the geography of a healthy stomach.

With the falling of the sun the climate of the country had changed. It was no longer blistering. You sat down for a moment and a shiver went up your spine. At noon I thought about all the lime-kilns I had ever met. Now I could hear the hickory nuts dropping in the crisp silence down in the old Missouri woods.

We struck the railroad and went faster. Since my first experience with railroad ties, I have continued to associate them with hunger. I need only look an ordinary railroad tie in the face to contract a wonderful appetite. It works on the principle of a memory system. So, as we put the ties behind us, I increased my order at that restaurant in the sweet little pedestrian's village of Goodale. "A couple of eggs on the side, waiter," I said half audibly to the petite woman in the white apron who served the tables in the restaurant there. She was very real to me. I could count the rings on her fingers; and when she smiled, I noted that her teeth were very white—doubtless they got that way from eating quantities and quantities of thick juicy beefsteak!

The track took a sudden turn ahead. "Around that bend," I said aloud, "lies Goodale." We went faster. We rounded the bend, only to see the dusky, heartachy, barren stretch.

"Railroads," explained I to myself, "have a way of going somewhere; it is one of their peculiarities." No doubt this track had been laid for the express purpose of guiding hungry folks to the hospitable little village. We plunged on for an hour. Meanwhile my orders to the trim little woman in the white apron increased steadily. She smiled broadly but winsomely, showing those charming beefsteak-polished teeth. They shone like a beacon ahead of me, for it was now dark.

Suddenly we came upon a signboard. We went up to it, struck a match, and read breathlessly—"Goodale."

We looked about us. Goodale was a switch and a box car.

I quoted,

Alas for the trim little lady with the white teeth and the smile and the beefsteak!

We said bitter things there in that waste about the man with the information. We loaded his memory with anathemas. One cannot eat a signboard, even with so inviting a name upon it. An idea struck me—it seemed a very brilliant one at the moment. I sat down and delivered myself of it to my companions, who also had lusted after the flesh-pots. "We have wronged that man with the information," said I. "He was no ordinary individual; he was a prophet: he simply got his dates mixed. In precisely one hundred years from now, there will be a town on this spot—and a restaurant! Shall we wait?"

They cursed me bitterly. I suspect neither of them is a philosopher. Thereat I proceeded to eat a thick juicy steak from the T-bone portion of an unborn steer, served by the trim little lady of a hundred years hence, there in that potential village of Goodale. And as I smoked my cigarette, I felt very thankful for all the beautiful things that do not exist.

And I slept that night in the great front bedroom, the ceiling of which is of diamond and turquoise.

AT last the sinuous yellow road dropped over the bluff rim and, to all appearances, dissolved into the sky—a gray-blue, genius-colored sky.

It was sundown, and this was the end of the trail for us. Beneath the bluff rim lay Benton. We flung ourselves down in the bunch-grass that whispered dryly in a cool wind fresh from the creeping night-shade. Now that Benton lay beneath us, I was in no hurry to look upon it.

Fort Benton? What a clarion cry that name had been to me! Old men—too old for voyages—had talked about this place; a long time ago, 'way down on the Kansas City docks, I had heard them. How far away it was then! Reach after reach, bend after bend, grunting, snoring, toiling, sparring over bars, bucking the currents, dodging the snags, went the snub-nosed steamers—brave little steamers!—forging on toward Fort Benton. And it was so very, very far away—half-way to the moon no doubt! St. Louis was indeed very far away. But Fort Benton!——

Well, they spoke of the Fort Benton traffic as "the mountain trade," and I had not then seen a mountain. You could stand on the very tallest building in Kansas City, and you could look and look and never see a mountain. And to think how far the brave little steamers had to go! How did they ever manage to get back?

But the old men on the docks—they had been there and all the way back, perhaps hundreds of times. And they were such heroes! Great paw-like hands they had, toughened with the gripping of cables; eyes that had that way of looking through and far beyond things. (Seamen and plainsmen have it.) And they had such romantic, crinkly, wrinkly, leathery faces. They got so on the way to Benton and back. And they talked about it—those old men lounging on the docks—because it was so far away and they were so old that they couldn't get there any more.

What a picture I made out of their kaleidoscopic chatter; beautifully inaccurate, impossibly romantic picture, in which big muscley men had fights with yawping painted savages that always got gloriously licked, in the approved story-book manner! I could shut my eyes and see it all very plainly, away off there half-way to the moon. And I used to wonder how my father could be such a strong man and never have any hankering to go up there at all! The two facts were quite incompatible. He should have been a captain and taken me on for cub pilot, or at least a "striker" engineer; though I wouldn't have objected seriously to the business of a cabin boy. I thought it would be very nice to engage in the mountain trade.

And then, after a while, in the new light that creeps in with years, I began to rearrange my picture of things up there; and Benton crept a wee bit closer—until I could see its four adobe walls and its two adobe bastions, stern with portholes, sitting like bulldogs at the opposite corners ready to bark at intruders. And in and out at the big gate went the trappers—sturdy, rough-necked, hirsute fellows in buckskins, with Northwest fusils on their shoulders; lean-bodied, capable fellows, with souls as lean as their bodies, survivors of long hard trails, men who could go far and eat little and never give up. I was very fond of that sort of man.

Little by little the picture grew. Indian bull boats flocked at the river front beneath the stern adobe walls; moored mackinaws swayed in the current, waiting to be loaded with peltries and loosed for the long drift back to the States; and the keel-boats, looking very fat and lazy, unloaded supplies in the late fall that were loaded at St. Louis in the early spring. And these had come all the way without the stroke of a piston or the crunch of a paddle-wheel or a pound of steam. Nothing but grit and man-muscle to drag them a small matter of two or three thousand miles up the current of the most eccentric old duffer of a river in the world!

What men it did take to do that! I saw them on the wild shelterless banks of the yellow flood—a score or so of them—stripped and sweating under the prairie sun, with the cordelle on their calloused shoulders, straightening out to the work like honest oxen. What males those cordelle men were—what stayers! Fed on wild, red meat, lean and round of waist, thick of chest, thewed for going on to the finish. Ten or fifteen miles a day and every inch a fight! Be sure they didn't do it merely for the two or three hundred dollars a year they got from the Company. They did it because they were that sort of men, and had to express themselves. Everything worth while is done that way.

Do they raise that breed now? Never doubt it! You need only find your keel-boats or their equivalents, and the men will come around for the job, I'm sure. But when you speak enthusiastically of the old Greek doers of things, I'd like to put in a few words for those old up-river men. They belong to the unwritten American epic.

And then the keel-boats and the bull-boats and the mackinaws and the up-river men flashed out—like a stereopticon picture when the man moves the slide; and I saw a little ragged village of log houses scattered along the water front. I saw the levees piled with merchandise, and a score or more of packets rushing fresh cargoes ashore—mates bawling commands down the gangplanks where the roustabouts came and went at a trot. Gold-mad hundreds thronged the wagon-rutted streets of this raw little village, the commercial center of a vast new empire. Six-horse freighters trundled away toward the gold fields; and others trundled in, their horses jaded with the precious freight they pulled. And I saw steamers dropping out for the long voyage back to the States, freighted with cargoes of gold dust—really truly story-book treasure-ships that would have made old Captain Kidd's men mad with delight.

As I lay dreaming in the bunch-grass, it all grew up so real that I had to get up and take my first look, half expecting to find it all there just as in the old days.

We stood at the rim of the bluff and looked down into a cup-like valley upon a quiet little village, winking with scattered lights in the gloaming. Past it swept the river—glazed with the twilight and silver-splotted with early stars.

This was Benton—it could have been almost any other town as well. And yet, once upon a time, it had filled my day-dreams with wonders—this place that seemed half-way to the moon.

The shrill shriek of a Great Northern locomotive, trundling freight cars through the gloom, gave the death-stroke to the old boy-dream. It was the cry of modernity. This boisterous, bustling, smoke-breathing thing, plunging through the night with flame in its throat, had made the change, dragged old Benton out of the far-off lunar regions and set what is left of it right down in the back yard of the world. Even a very little boy could get there now.

"And yet," thought I, as we set out rapidly for the village in the valley, "the difference between the poetry of mackinaws and Great Northern locomotives is merely a matter of perspective. If those old cordelle men could only come back for a while from their Walhalla, how they would crowd about that wind-splitting, fire-eating, iron beast, panting from its long run, and catching its breath for another plunge into the waste places and the night! And I? I would be gazing wide-mouthed at the cordelle men. It's only the human curiosity about the other side of the moon. How perfect the nights would be if we could only see that lost Pleiad!"

Ankle-deep in the powdery sand, we entered the little town with its business row facing the water front. One glance at the empty levees told you of the town's dead glory. Not a steamboat's stacks, blackening in the gloom, broke the peaceful glitter of the river under the stars. But along the sidewalk where the electric-lighted bar-rooms buzzed and hummed, brawny cow-men, booted and spurred, lounged about, talking in that odd but not unpleasant Western English that could almost be called a dialect.

But it was not the Benton of the cow-men that I felt about me. It was still for me the Benton of the fur trade and the steamboats and the gold rush—my boyhood's Benton half-way to the moon—the ghost of a dead town.

At Goodale I had sought a substantial town and found a visionary one. At Benton I had sought a visionary town and found a substantial one. Philosophy was plainly indicated as the proper thing. And, after all, a steaming plate of lamp chops in a Chinese chuck-house of a substantial though disappointing town, is more acceptable to even a dreamer than the visionary beefsteak I ate out there in that latent restaurant of a potential village.

This was a comfortable thought; and for a quarter of an hour, the far weird cry of things that are no more, was of no avail. The rapid music of knife and fork drowned out the asthmatic snoring of the ghostly packets that buck the stream no more. How grub does win against sentiment!

Swallowing the last of the chops, "Where will I find the ruins of the old fort?" I asked of my bronze-faced neighbor across the wreck of supper. He looked bored and stiffened a horny practical thumb in the general direction of the ruins. "Over there," he said laconically.

I caught myself wondering if a modern Athenian would thus carelessly direct you to the Acropolis. Is the comparison faulty? Surely a ruin is sacred only for what men did there. We are indeed a headlong race. We keep our ruins behind us. Perhaps that is why we get somewhere. And yet, what beauty blooms flowerlike to the backward gaze! Music and poetry—all the deepest, purest sentiments of the heart—are fed greatly upon the memory of the things that were but can never be again. Mnemosyne is the mother of all the Muses.

I got up and went out. By the light of a thin moon, I found the place "over there." An odd, pathetic little ruin it is, to be sure. Nothing imposing about it. It doesn't compel through admiration: it woos through pity—the great, impersonal kind of pity.

Browning tells about all there is to tell about it, though he never heard of it; only they called it a "bastion" in the old days—the little square adobe blockhouse that won't stand much longer. One crumbling bastion and two gaunt fragments of adobe walls in a waste of sand beside the river—that's Fort Benton.

A thin pale grudging strip of moon lit it up: just the moon by which to see ruins—a moon for backward looking and regrets. A full round love-moon wouldn't have served at all.

Out of pure moon-haze I restored the walls of the house where the bourgeois lived. The fireplace and the great mud chimney are still there, and the smut of the old log fires still clings inside. The man who sat before that hearth was an American king. A simple word of command spoken in that room was the thunder of the law in the wilderness about, and men obeyed. There's a bat living there now. He tumbled about me in the dull light, filling the silence with the harsh whir of pinions.

I thought about that night a long, long time ago when all the people under the protection of the newly erected fort, gathered here for a house-warming. How clearly I could hear that squawking, squeaking, good-natured fiddle and the din of dancing feet! Only the sound got mixed up with the dim, weird moonlight, until you didn't know whether you were hearing or seeing or feeling it—the music of the fiddles and the feet. Oh, the dim far music!

I thought about the other ruins of the world, the exploited, tourist-haunted ruins; and I wondered why the others attract so much attention while this one attracts practically none at all. How they do dig after old Troy—poor old long-buried, much-abused Troy! And nobody even cares to steal a brick from this ruined citadel that took so great a part in the American epic. Indeed, you would not be obliged to steal a brick; there are no guards.

Some one has said that the history of our country as taught in the common schools is the history of a narrow strip of land along the Atlantic coast. The statement is significant. The average school-teacher knows very little about Fort Benton, I suspect.

And yet, one of the most tremendous of all human movements centered about it—the movement that brought about the settlement of the Northwest. One of these days they will plant a potato patch there!

But modern Benton?

Get on a train in the East, snuggle up in your berth, plunge on to the Western coast, and you run through the real West in the night. They are getting Eastern out there at the rim of the big sea. Benton is in the West—the big, free, heart-winning West; and it gives promise of staying there for a while yet.

Charter a bronco and canter out across the river for an hour, and it will be very plain to you that the romantic West still lives—the West of the cowboy and the bronco and the steer. Not the average story-book West, to be sure. Perhaps that West never existed. But it is the West that has bred and is still breeding a race of men as beautiful in a virile way (and how else should men be beautiful?) as this dear old mother of an Earth ever suckled.

I stood once on the yellow slope of a hill and watched a round-up outfit passing in the gulch below. Four-horse freighters grumbling up the dusty trail; cook wagons trundling after; whips popping over the sweating teams; a hundred or more saddle ponies trailing after in rolling clouds of glinting dust; a score of bronze-faced, hard-fisted outriders, mounted on gaunt, tough, wise little horses—such strong, outdoor, masterful Americans, truly beautiful in a big manly way!

The sight of it all put that glorious little achy feeling in my throat that you get when they start the fife and drum, or when a cavalry column wheels at the word of command, or when a regiment swings past with even tread, or when you stand on a dock and watch a liner dropping out into the fog. It's the feeling that you're a man and mighty proud of it. But somehow it always makes you just a little sad.

I felt proud of that bunch of strong capable fellows—proud as though I had created them myself.

And once again the glorious little achy feeling in the throat came. The Congressman from Choteau County had returned from Washington with fresh laurels; and Benton turned out to welcome her Great Man. Down the dusty, poorly lighted, front street came the little band—a shirt-sleeved squad. Halting under the dingy glow of a corner street-lamp, they struck up the best-intentioned, noisiest noise I ever heard. The tuba raced lumberingly after the galloping cornet, that ran neck-and-neck with the wheezing clarinet; and the drums beat up behind, pounding like the hoofs of stiff-kneed horses half a stretch behind.

It was a mad, exciting race of sounds—a sort of handicap. The circular glow of the street-lamp became the social center of Benton. At last the mad race was ended. I think it was the cornet that won, with the clarinet a close second. The tuba, as I recollect it, complacently claimed third money, and the bass-drum finished last with a shameless, resolute boom!

A great hoarse cry went up—probably for the winning cornet; a big-lunged, generous, warrior cry that made you think of a cavalry charge in the face of bayonets. And the shirt-sleeved band swung off down the street in the direction of the little cottage where the Great Man lived. All Benton fell in behind—clerks and bar-keeps and sheepmen and cowboys tumbling into fours. Under the yellow flare of the kerosene torches they went down the street like a campaigning company in rout step, scattering din and dust.

Great, deep-chested, happy-looking, open air fellows, they were; big lovers, big haters, good laughers, eaters, drinkers—and every one of them potentially a fighting man.

And suddenly, as I watched them pass, something deep down in me cried out: "Great God! What a fighting force we can drum up out of the cactus and the sagebrush when the time comes!" And when I looked again, not one of the sun-bronzed faces was strange to me, but every one was the face of a brother. Choteau's Congressman was my Congressman! Benton's Great Man was my Great Man! I fell into line alongside a big bronco-buster with his high-heeled boots and his clanking spurs and his bandy-legged, firm-footed horseman's stride. Thirty yards farther on we were old comrades. That is the Western way.

Once again the little band struck up a march, which was very little more than a rhythmic snarling and booming of the drums, with now and then the shrill savage cry of the clarinet stabbing the general dim. Irresistibly the whole line swung into step.

What is it about the rhythmic stride of many men down a dusty road that grips you by the throat and makes your lungs feel like overcharged balloons? I felt something like the maddening, irritating tang of powder-smoke in my throat. Trumpet cries that I had never heard, yet somehow dimly remembered, wakened in the night about us—far and faint, but haughty with command. It took very little imagination for me to feel the whirlwind of battles I may never know, to hear the harsh metallic snarl of high-power bullets I may never face. For, marching there in the dusty, torch-painted night, with that ragged procession of Westerners, a deep sense of the essential comradeship of free men had come upon me; and I could think of these men in no other way than as potential fighting men—the stern hard stuff with which you build and keep your empires. What a row Napoleon could have kicked up with half a million of these sagebrush boys to fling foeward under his cannon-clouds!

We reached the cottage of the Great Man with the fresh laurels. He met us at the gate. He called us Jim and Bill and Frank and Kid something or other. We called him Charlie. And he wasn't the least bit stiff or proud, though we hadn't the least doubt that half of Washington was in tears at his departure for the West.

The sudden flare of a torch betrayed his moist eyes as he told us how he loved us. And I'm sure he meant it. He said, with that Western drawl of his: "Boys, while I was back there trying to do a little something for you in Congress, I heard a lot of swell bands; but I didn't hear any such music as this little old band of ours has made to-night!" The unintentional humor somehow didn't make you want to laugh at all.

We're all riding with his outfit; and next year we're going to send Charlie back East again. May we all die sheepmen if we don't—and that's the limit in Montana!

Talking about sheepmen, reminds me of Joe, the big bronco-buster, and his mot. I was doing the town with Joe, and he was carefully educating me in the Western mysteries. He told me all about "day-wranglers" and "night-hawks" and "war-bags" and "round-ups"; showed me how to tie a "bull-noose" and a "sheep-shank" and a "Mexican hacamore"; put me onto the twist-of-the-wrist and the quick arm-thrust that puts half-hitches 'round a steer's legs; showed me how a cowboy makes dance music with a broom and a mouth-harp—and many other wonderful feats, none of which I can myself perform.

I wanted to feel the mettle of the big typical fellow, and so I said playfully: "Say, Joe, come to confession—you're a sheepman, now aren't you?"

He clanked down a glass of long-range liquid, and glared down at me with a monitory forefinger pointing straight between my eyes: "Now you look here, Shorty," he drawled; "you're a friend of mine, and whatever you say goes, as long as I ain't all caved in! But you cut that out, and don't you say that out loud again, or you and me'll be having to scrap the whole outfit!"

He resumed his glass. I told him, still playfully, that a lot of mighty good poetry had been written about sheep and sheepmen and crooks and lambs and things like that, and that I considered my question complimentary.

"You're talkin' about sheepmen in the old country, Shorty," he drawled. "There ain't any cattle ranges there, you know. Do you know the difference between a sheepman in Scotland, say, and in Montana?"

I did not.

"Well," he proceeded, "over in Scotland when a feller sees a sheepman coming down the road with his sheep, he says: 'Behold the gentle shepherd with his fleecy flock!' That's poetry. Now in Montana, that same feller says, when he sees the same feller coming over a ridge with the same sheep: 'Look at that crazy blankety-blank with his woolies!' That's fact. You mind what I say, or you'll get spurred."

I don't quite agree with Joe, however. Once, lying in my tent across the river, I looked out over the breaks through that strange purple moonlight, such as I had always believed to exist only in the staging of a melodrama, and saw four thousand sheep descending to the ferry.

Like lava from a crater they poured over the slope above me; and above them, seeming prodigiously big against the weird sky, went the sheepman with his staff in his hand and a war-bag over his arm, while at his heels a wise collie followed. It was a picture done by chance very much as Millet could have done it. And somehow Joe's mot couldn't stand before that picture.

There is indeed a big Pindaric sort of poetry about a plunging mass of cattle. And just as truly there is a sort of Theocritus poetry about sheep. Only in the latter case, the poetical vanishing point is farther away for me than is the case with cattle. I think I couldn't write very good verses about a flock of sheep, unless I were at least five hundred yards away from them. I haven't figured the exact distance as yet. But when you have a large flock of sheep camping about you all night, making you eat fine sand and driving you mad with that most idiotic of all noises (which happened once to me), you don't get up in the morning quoting Theocritus. You remember Joe's mot!

We found a convenient gravel bar on the farther side of the river, where we established our navy-yard. There we proceeded to set up the keel of the Atom I—a twenty-foot canoe with forty-inch beam, lightly ribbed with oak and planked with quarter-inch cypress.

No sooner had we screwed up the bolts in the keel, than our ship-yard became a sort of free information bureau. Every evening the cable ferry brought over a contingent of well-wishers, who were ardent in their desire to encourage us in our undertaking, which was no less than that of making a toboggan slide down the roof of the continent.

The salient weakness of the genus homo, it has always seemed to me, is an overwhelming desire to give advice. Through several weeks of toil, we were treated to a most liberal education on marine matters. It appeared that we had been laboring under a fatal misunderstanding regarding the general subject of navigation. Our style of boat was indeed admirable—for a lake, if you please, but—well, of course, they did not wish to discourage us. It was quite possible that we were unacquainted with the Upper Missouri. Now the Upper River (hanging out that bleached rag of a sympathetic smile), the Upper River was not the Lower River, you know. (That really did seem remarkably true, and we became alarmed.) The Upper River, mind you, was terriffic. Why, those frail ribs and that impossible planking would go to pieces on the first rock—like an egshell! Of course, we were free to do as we pleased—they would not discourage us for the world. And the engine! Gracious! Such a boat would never stand the vibration of a four-horse, high-speed engine driving a fourteen-inch screw! It appeared plainly that we were almost criminally wrong in all our calculations. Shamefacedly we continued to drive nails into the impossible hull, knowing full well—poor misguided heroes—that we were only fashioning a death trap! There could be no doubt about it. The free information bureau was unanimous. It was all very pathetic. Nothing but the tonic of an habitual morning swim in the clear cold river kept us game in the face of the inevitable!

We saw it all. With a sort of forlorn cannon-torn-cavalry-column hope we pushed on with the fatal work. Never before did I appreciate old Job in the clutches of good advice. I used to accuse him of rabbit blood. In the light of experience, I wish to record the fact that I beg his pardon. He was in the house of his friends. I think Job and I understand each other better now. It was not the boils, but the free advice!

At last the final nail was driven and clenched, the canvas glued on and ironed, the engine installed. The trim, slim little craft with her admirable speed lines, tapering fore and aft like a fish, lay on the ways ready for the plunge.

We had arranged to christen her with beer. The Kid stood at the prow with the bottle poised, awaiting his cue. The little Cornishman knelt at the prow. He was not bowed in prayer. He was holding a bucket under the soon-to-be-broken bottle. "For," said he, "in a country where beer is so dear and advice so cheap, let us save the beer that we may be strong to stand the advice!"

The argument was inded Socratic.

"And now, little boat," said I, in that dark brown tone of voice of which I am particularly proud, "be a good girl! Deliver me not unto the laughter of my good advisers. I christen thee Atom!"

The bottle broke—directly above that bucket.

And now before us lay the impossible as plainly pointed out, not only by local talent, but by no less a man that the august captain of a government snag-boat. Several weeks before the launching, an event had taken place at Benton. The first steamboat for sixteen years tied up there one evening. She was a government snag-boat. Now a government snag-boat may be defined as a boat maintained by the government for the sole purpose of sailing the river and dodging snags. This particular snag-boat, I learned afterward in the course of a long cruise behind her, holds the snag-boat record. I consider her pilot a truly remarkable man. He seemed to have dodged them all.

All Benton turned out to view the big red and white government steamer. There was something almost pathetic about the public demonstration when you thought of the good old steamboat days. During her one day's visit to the town, I met the captain.

He was very stiff and proud. He awed me. I stood before him fumbling my hat. Said I to myself: "The personage before me is more than a snag-boat captain. This is none other than the gentleman who invented the Missouri River. No doubt even now he carries the patent in his pocket!"

"Going down river in a power canoe, eh?" he growled, regarding me critically. "Well, you'll never get down!"

"That so?" croaked I, endeavoring to swallow my Adam's apple.

"No, you won't!"

"Why?" ventured I timidly, almost pleadingly; "isn't there—uh—isn't there—uh—water enough?"

"Water enough—yes!" growled the personage who invented the longest river in the world and therefore knew what he was talking about. "Plenty of water—but you won't find it!"

Now as the Atom slid into the stream, I thought of the captain's words. Since that time the river had fallen three feet. We drew eighteen inches.

Sixty-five days after that oraculous utterance of the captain, the Kid and I, half stripped, sun-burned, sweating at the oars, were forging slowly against a head wind at the mouth of the Cheyenne, sixteen hundred miles below the head of navigation. A big white and red steamer was creeping up stream over the shallow crossing of the Cheyenne's bar, sounding every foot of the water fallen far below the usual summer level.

It was the snag-boat. Crossing her bows and drifting past her slowly, I stood up and shouted to the party in the pilot house:

"I want to speak to the captain."

He came out on the hurricane deck—the man who invented the river. He was still stiff and proud, but a swift smile crossed his face as he looked down upon us, half-naked and sun-blackened there in our dinky little craft.

"Captain," I cried, and perhaps there was the least vainglory in me; "I talked to you at Benton."

"Yes, sir."

"Well, I have found that water!"

TELL a Teuton that he can't, and very likely he will show you that he can. It's in the blood. Between the prophecy of the snag-boat captain and my vainglorious answer at the Cheyenne crossing, I learned to respect the words of the man who invented the eccentric old river. In the face of heavy head winds, I quoted the words, "You'll never get down"—and they bit deep like whip lashes. On many a sand-bar and gravel reef, with the channel far away, I heard the words, "Plenty of water, yes, but you won't find it!" And always something stronger than my muscles cried out within me: "The devil I won't, O, you inventor of rain-water creeks!" Hour by hour, day by day, against almost continual head winds and with the lowest water in years, that discouraging prophecy invaded me and was repulsed. And that is why we have pessimists in the world. A pessimist is merely a counter-irritant.

I stood on the bank for some time after the Atom I slid into the water, admiring her truly beautiful lines. Once I was captain of a trunk lid that sailed a frog-pond down in Kansas City; and at that time I thought I knew the meaning of pride. I did not. All three of us were a bit puffed up over that boat. Something of that ride that goes before a fall awoke in my captain's breast as I loved her with my eyes—that trim, slim speed-thing, tugging at her forward line, graceful and slender and strong and fleet as a Diana.

I said at last: "I will now get in her, drop down to the town landing, and proceed to put to shame a few of these local motor-tubs that make so much fuss and don't go anywhere!"

I loved her as a man should love all things that are swift and strong and honest, keen for marks and goals—a big, clean-limbed, thoroughbred horse that will break his heart to get under the wire first; a high-power rifle, slim of muzzle, thick of breech, with its wicked little throaty cry, doing its business over a flat trajectory a thousand yards away: I love her as a man should love those. Little did I dream that she would betray me.

I took in the line and went aboard. At that moment I almost understood the snag-boat captain's bearing. To be master of the Atom I seemed quite enough; but to be the really truly captain of a big red and white snag-boat—it must have been overwhelming!

I dropped out into the current that, fresh from its plunge of four hundred feet in sixteen miles, ran briskly. Everything was in readiness. I meant to put a crimp in the vanity of that free-information bureau.

I turned on the switch, opened the needle valve, swung the throttle over to the notch numbered with a big "2." I placed the crank on the wheel and gave it a vigorous turn.

"Poof!" said the engine sweetly, and the kind word encouraged me immensely. Again I cranked.

"Poof! Poof!"

It seemed that I had somehow misunderstood the former communication, and it was therefore repeated with emphasis. Like a model father who walks the floor with the weeping child, tenderly seeking the offending pin, I looked over the engine. "What have I neglected?" said I. I intended to be quite logical and fair in the matter.

I once presided over a country newspaper that ran its presses with a gasoline engine with a most decided artistic temperament. That engine used to have a way of communing silently with its own soul right in the middle of press day. I remembered this with forebodings. I remembered how firm but kind I was obliged to be with that old engine. I remembered how it always put its hands in its pockets and took an extended vacation every time I swore at it. I decided to be nothing but a perfect gentleman with this engine. I even endeavored to be a jovial good fellow.

"What is it, Little One?" said I mentally; "does its little carburetor hurt it? Or did the bad man strangle it with that horrid old gasoline?"

I tenderly jiggled its air valve, fiddled gently with its spark-control lever. I cranked it again. It barked at me like a dog! I had been kind to it, and it barked right in my face. I wanted to slap it. I lifted my eyes and saw that the rapid current would soon carry me past the town landing. I seized a paddle and shoved her in. Of course, a member of the free-information bureau was at the landing. He had with him a bland smile and a choice bit of information.

"Having trouble with your engine, aren't you?" he said as I leaped ashore with the line. "There must be something wrong with it!" The remark was indeed illuminating. It struck me with the force of an inspiration. It seemed so true.