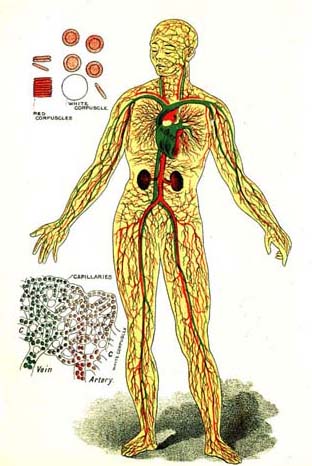

PLATE 1. THE CIRCULATION.

Project Gutenberg's First Book in Physiology and Hygiene, by J.H. Kellogg This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: First Book in Physiology and Hygiene Author: J.H. Kellogg Release Date: December 21, 2005 [EBook #17367] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FIRST BOOK IN PHYSIOLOGY *** Produced by Suzanne Lybarger, Janet Blenkinship, Brian Janes and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, THE AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH

ASSOCIATION, SOCIÉTÉ D'HYGIÈNE OF FRANCE, BRITISH AND AMERICAN

ASSOCIATIONS FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE, MICHIGAN

STATE BOARD OF HEALTH, ETC.

NEW AND REVISED EDITION

NEW YORK CINCINNATI CHICAGO

AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY

Copyright, 1887, by Harper & Brothers.

Copyright, 1888, by Harper & Brothers

All rights reserved.

W.P. 7

This book is intended for children. The special objects which the author has aimed to accomplish in the preparation of the work have been:

1. To present as fully as possible and proper in a work of this character a statement of the laws of healthful living, giving such special prominence to the subject of stimulants and narcotics as its recognized importance and the recent laws relating to the study of this branch of hygiene demand.

2. To present in a simple manner such anatomical and physiological facts as shall give the child a good fundamental knowledge of the structure and functions of the human body.

3. To present each topic in such clear and simple language as to enable the pupil to comprehend the subject-matter with little aid from the teacher; and to observe in the manner of presentation the principle that the things to be studied should be placed before the mind of the child before they are named. A natural and logical order has been observed in the sequence of topics. Technical terms have been used very sparingly, and only in their natural order, and are then fully explained and their pronunciation indicated, so that it is not thought necessary to append a glossary.

[Pg iii]4. To present the subjects of Physiology and Hygiene in the light of the most recent authentic researches in these branches of science, and to avoid the numerous errors which have for many years been current in the school literature of these subjects.

There is no subject in the presentation of which object-teaching may be employed with greater facility and profit than in teaching Physiology, and none which may be more advantageously impressed upon the student's mind by means of simple experimentation than the subject of Hygiene. Every teacher who uses this book is urgently requested to supplement each lesson by the use of object-teaching or experiments. A great number of simple experiments illustrative of both Physiology and Hygiene may be readily arranged. Many little experiments are suggested in the text, which should invariably be made before the class, each member of which should also be encouraged to repeat them at home.

It is also most desirable that the teacher should have the aid of suitable charts and models.

In conclusion, the author would acknowledge his indebtedness for a large number of useful suggestions and criticisms to several medical friends and experienced teachers, and especially to Prof. Henry Sewall, of the University of Michigan, for criticisms of the portions of the work relating to Physiology.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| To the Teacher | iii | |

| I. | The House we Live in | 1 |

| II. | A General View of the Body | 5 |

| III. | The Inside of the Body | 7 |

| IV. | Our Foods | 11 |

| V. | Unhealthful Foods | 14 |

| VI. | Our Drinks | 19 |

| VII. | How we Digest | 27 |

| VIII. | Digestion of a Mouthful of Bread | 35 |

| IX. | Bad Habits in Eating | 39 |

| X. | A Drop of Blood | 46 |

| XI. | Why the Heart Beats | 48 |

| XII. | How to Keep the Heart and the Blood Healthy | 56 |

| XIII. | Why and How we Breathe | 63 |

| XIV. | How to Keep the Lungs Healthy | 75 |

| XV. | The Skin and What it Does | 81 |

| XVI. | How to Take Care of the Skin | 88 |

| XVII. | The Kidneys and their Work | 91 |

| XVIII. | Our Bones and their Uses | 93 |

| XIX. | How to Keep the Bones Healthy | 100 |

| XX. | The Muscles, and How we Use Them | 105 |

| XXI. | How to Keep the Muscles Healthy | 109 |

| XXII. | How we Feel and Think | 115 |

| XXIII. | How to Keep the Brain and Nerves Healthy | 126 |

| XXIV. | Bad Effects of Alcohol upon the Brain and Nerves | 130 |

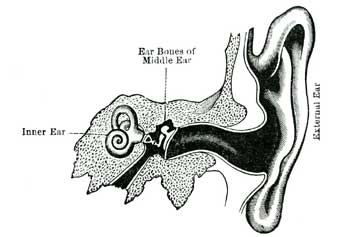

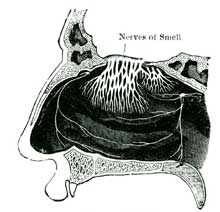

| XXV. | How we Hear, See, Smell, Taste; and Feel | 138 |

| XXVI. | Alcohol | 154 |

| Questions for Review | 170 | |

1. Object of this Book.—The object of this book is to tell the little boys and girls who read it about a wonderful house. You have all seen some very beautiful houses. Perhaps they were made of brick or stone, with fine porches, having around them tall shade trees, smooth lawns, pretty flower-beds, walks, and sparkling fountains.

2. Perhaps some of you live in such a house, or have visited some friend who does. If so, you know that the inside of the house is even more beautiful than the outside. There are elegant chairs and sofas in the rooms, rich carpets and rugs on the floors, fine mirrors and beautiful [Pg 2]pictures upon the walls—everything one could wish to have in a house. Do you not think such a house a nice one to live in?

3. The Body is Like a House.—Each of us has a house of his own which is far more wonderful and more curious than the grandest palace ever built. It is not a very large house. It has just room enough in it for one person. This house, which belongs to each one of us, is called the body.

4. What is a Machine?—Do you know what a machine is? Men make machines to help them work and to do many useful things. A wheelbarrow or a wagon is a machine to carry loads. A sewing-machine helps to make garments for us to wear. Clocks and watches are machines for keeping time.

5. A Machine has Different Parts.—A wheelbarrow has a box in which to carry things, two handles to hold by, and a wheel for rolling it along. Some machines, like wheelbarrows and wagons, have but few parts, and it is very easy for us to learn how they work. But there are other machines, like watches and sewing-machines, which have many different parts, and it is more difficult to learn all about them and what they do.

6. The Body is Like a Machine.—In some ways the body is more like a machine than like [Pg 3]a house. It has many different parts which are made to do a great many different kinds of work. We see with our eyes, hear with our ears, walk with our legs and feet, and do a great many things with our hands. If you have ever seen the inside of a watch or a clock you know how many curious little wheels it has. And yet a watch or a clock can do but one thing, and that is to tell us the time of day. The body has a great many more parts than a watch has, and for this reason the body can do many more things than a watch can do. It is more difficult, too, to learn about the body than about a watch.

7. If we want to know all about a machine and how it works, we must study all its different parts and learn how they are put together, and what each part does. Then, if we want the machine to work well and to last a long time, we must know how to use it and how to take proper care of it. Do you think your watch would keep the time well if you should neglect to wind it, or if you should break any of its wheels?

8. It is just the same with the human machine which we call the body. We must learn its parts, and what they are for, how they are made, how they are put together, and how they work. Then we must learn how to take proper care of the [Pg 4]body, so that its parts will be able to work well and last a long time.

9. Each part of the body which is made to do some special kind of work is called an organ. The eye, the ear, the nose, a hand, an arm, any part of the body that does something, is an organ.

10. The study of the various parts of the body and how they are put together is anatomy (a-nat´-o-my). The study of what each part of the body does is physiology (phys-i-ol´-o-gy). The study of how to take care of the body is hygiene (hy´-jeen).

1. The body is something like a house. It has an outside and an inside; it has hollow places inside of it, and there are many wonderful things in them.

2. The body is also like a wonderful machine.

3. It is necessary to take good care of the body in order to keep it well and useful, just as we would take good care of a machine to keep it from wearing out too soon.

4. The body has many different parts, called organs, each of which has some particular work to do.

5. In learning about the body, we have to study anatomy, physiology, and hygiene.

6. The study of the various parts of the body, how they are formed and joined together, is anatomy. Physiology tells us what the body does, hygiene tells us how to take care of it.

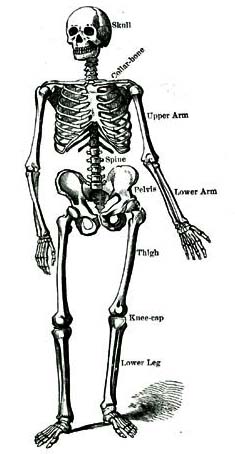

1. Parts of the Body.—What do we call the main part of a tree? The trunk, you say. The main part of the body is also called its trunk. There are two arms and two legs growing out of the human trunk. The branches of a tree we call limbs, and so we speak of the arms and legs as limbs. We sometimes call the arms the upper extremities, and the legs the lower extremities. At the top of the trunk is the head.

2. Names of the Parts.—Now let us look more closely at these different parts. As we speak the name of each part, let each one touch that part of himself which is named. We will begin with the head. The chief parts of the head are the skull and the face. The forehead, the temples, the cheeks, the eyes, the ears, the nose, the mouth, and the chin are parts of the face.

3. The chief parts of the trunk are the chest, the abdomen (ab-do´-men), and the backbone. The head is joined to the trunk by the neck.

4. Each arm has a shoulder, upper-arm, fore-[Pg 6]arm, wrist, and hand. The fingers are a part of the hand.

5. Each leg has a hip, thigh, lower leg, ankle, and foot. The toes are a part of the foot.

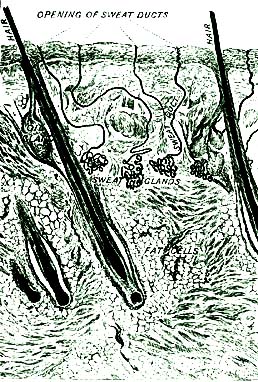

6. Our hands and face and the whole body are covered with something as soft and smooth as the finest silk. It is the skin. What is it that grows from the skin on the head? and what at the ends of the fingers and the toes? We shall learn more about the skin, the hair, and the nails in another lesson.

7. The body has two sides, the right side and the left side, which are alike. We have two eyes, two ears, two arms, etc. We have but one nose, one mouth, and one chin, but each of these organs has two halves, which are just alike.

1. The body has a head and trunk, two arms, and two legs.

2. The parts of the head are the skull and face. The forehead, temples, cheeks, eyes, ears, nose, mouth and chin are parts of the face.

3. The parts of the trunk are, the chest, abdomen, and backbone. The neck joins the head and trunk.

4. Each arm has a shoulder, upper-arm, fore-arm, wrist, and hand. The fingers belong to the hand.

5. Each leg has a hip, thigh, lower leg, ankle, and foot. The toes belong to the foot.

6. The whole body is covered by the skin.

7. The two sides of the body are alike.

1. Thus far we have taken only a brief look at the outside of the body, just as if we had looked at the case of a watch, and of course we have found out very little about its many wonderful parts. Very likely you want to ask a great many questions, such as, How does the inside of the body look? What is in the skull? What is in the chest? What is in the abdomen? Why do we eat and drink? Why do we become hungry and thirsty? What makes us tired and sleepy? How do we keep warm? Why do we breathe? How do we grow? How do we move about? How do we talk, laugh, and sing? How do we see, hear, feel, taste, and smell? How do we remember, think, and reason? All these, and a great many more interesting questions, you will find answered in the following lessons, if you study each one well.

2. When we study the inside of the body, we begin to understand how wonderfully we are made. We cannot all see the inside of the body, [Pg 8]and it is not necessary that we should do so. Many learned men have spent their whole lives in seeking to find out all about our bodies and the bodies of various animals.

3. The Bones.—If you take hold of your arm, it seems soft on the outside; and if you press upon it, you will feel something hard inside. The soft part is called flesh. The hard part is called bone. If you wish, you can easily get one of the bones of an animal at the butcher's shop, or you may find one in the fields.

4. The Skeleton.—All the bones of an animal, when placed properly together, have nearly the shape of the body, and are called the skeleton (skel´-e-ton). The skeleton forms the framework of the body, just as the heavy timbers of a house form its framework. It supports all the parts.

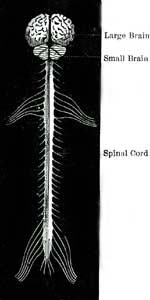

5. The Skull.—The bony part of the head is called the skull. In the skull is a hollow place or chamber. You know that a rich man often has a strong room or box in his fine house, in which to keep his gold and other valuable things. The chamber in the skull is the strong-room of the body. It has strong, tough walls of bone, and contains the brain. The brain is the most important, and also the most tender and delicate organ in the whole body. This is why it is so carefully guarded from injury.

[Pg 9]6. The Backbone.—The framework of the back is called the backbone. This is not a single bone, but a row of bones arranged one above another. Each bone has a hole through it, about as large as one of your fingers. A large branch from the brain, called the spinal cord, runs down through the middle of the backbone, so that the separate bones look as if they were strung on the spinal cord, like beads on a string.

7. The Trunk.—The trunk of the body, like the skull, is hollow. Its walls are formed partly by the backbone and the ribs and partly by flesh. A fleshy wall divides the hollow of the trunk into two parts, an upper chamber called the chest, and a lower called the abdomen.

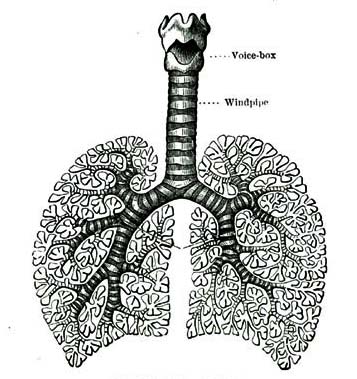

8. The Lungs and Heart.—The chest contains a pair of organs called the lungs, with which we breathe. It also contains something which we can feel beating at the left side. This is the heart. The heart lies between the two lungs, and a little to the left side.

9. The Stomach and Liver.—In the abdomen are some very wonderful organs that do different kinds of work for the body. Among them are the stomach, the bowels, and the liver. There are, also, other organs whose names we shall learn when we come to study them.

10. Care of the Body.—We have only begun [Pg 10]to study the beautiful house in which we live, and yet have we not learned enough to show us how great and wise is the Creator who made us and all the wonderful machinery within our bodies? If some one should give you a beautiful present, would you treat it carelessly and spoil it, or would you take good care of it and keep it nice as long as possible? Ought we not to take such care of our bodies as to keep them in that perfect and beautiful condition in which our kind and good Creator gave them to us?

1. The body has a framework, called the skeleton.

2. The skeleton is made up of many different parts, each of which is called a bone.

3. The bones are covered by the flesh.

4. The bones of the head form the skull, which is hollow and contains the brain.

5. A row of bones arranged in the back, one above another, forms the backbone. The backbone has a canal running through it lengthwise, in which lies the spinal cord.

6. The trunk is hollow, and has two chambers, one called the cavity of the chest, and the other the cavity of the abdomen.

7. The chest contains the two lungs and the heart.

8. The abdomen contains the stomach, liver, and many other very important organs.

9. Is it not our duty to take good care of our bodies as we would of some nice present from a friend?

1. We all know very well that if we do not eat we shall rapidly lose in weight, and become very weak and feeble. Did you ever think how much one eats in the course of a lifetime? Let us see if we can figure it up. How much do you suppose a boy eats in a day? Let us say two pounds. How much does he eat in a year? There are three hundred and sixty-five days in a year; 365 multiplied by 2 equals 730. So a boy eats a good many times his own weight in a year. How much would a person eat in fifty years?

2. Our bodies are composed of what we eat. If we eat bad food, our bodies will be made out of poor material, and will not be able to do their work well. So you see how important it is to learn something about our foods. We ought to know what things are good for us to eat, and what will do us harm.

3. Foods and Poisons.—Foods are those substances which nourish the body and keep it in good working order.

[Pg 12]4. Our foods are obtained from both animals and plants. All food really comes from plants, however, since those animals which we sometimes use as food themselves live upon the vegetables which they eat. For example, the ox and the cow eat grass and furnish us beef and milk. Chickens eat corn and other grains, and supply us with eggs.

5. The principal animal foods are milk, cheese, eggs, and the different kinds of flesh—beef, mutton, pork, fish, fowl, and wild game.

We obtain a great many more kinds of food from plants than from animals. Most plant foods are included in three classes—fruits, grains, and vegetables.

6. Fruits are the fleshy parts of plants which contain the seeds. Our most common fruits are apples, pears, peaches, plums, cherries, and various kinds of nuts. Perhaps you know of some other kinds of fruits besides those mentioned. Your teacher will tell you that tomatoes, watermelons, and pumpkins are really fruits, though they are not generally so called.

7. The seeds of grass-like plants are known as grains, of which we have wheat, rye, barley, corn, and rice. There are a few seeds that grow in pods, such as pease and beans, which somewhat resemble grains.

[Pg 13]8. We eat the leaves, stems, or roots of some plants, as cabbages, celery, turnips, and potatoes. Foods of this kind are called vegetables.

9. There are other things, which, if we eat or drink them, will make us sick or otherwise do us harm. These are called poisons. Only such food as is pure and free from poisons is good or safe for us to use.

10. Narcotics and Stimulants.—There are a number of substances known as narcotics and stimulants, which, from their effects upon the body, may be classed as poisons. Tobacco, opium, alcohol, and chloral are included in this class. Death has often been caused by taking small quantities of any of these poisonous drugs. We shall learn more of the effects of tobacco and alcohol in future lessons.

1. Our bodies are made of what we eat.

2. Things which will help us to grow strong and well, if we eat them, are foods.

3. We get foods from plants and animals.

4. There are several kinds of animal foods, and three classes of plant foods—fruits, grains, and vegetables.

5. Things which make us sick when we eat them, are poisons.

1. Most persons eat many things which are not good for them. Some people do not stop to think whether what they eat is good for them or likely to do them harm. Sometimes, without knowing it, we eat things which are harmful to us. Do you not think that we should try to learn what is good to eat and what is not good, and then be very careful not to eat anything which is likely to do us harm?

2. Diseased Foods.—When a person is sick, he is said to be diseased. Animals are sometimes sick or diseased. Vegetables are also sometimes diseased. Animals and vegetables that are diseased are not good for food. Dishonest men, however, sometimes sell them to those who do not know that they are unfit to be eaten.

3. Pork, the flesh of the hog, is more likely to be diseased than any other kind of animal food.

4. Beef and mutton may be diseased also. Sheep and cattle are sometimes sick of diseases [Pg 15]very much like those which human beings have. Meat which is pale, yellowish, or of a dark red color, is unhealthful, and should not be eaten. Meat should never be eaten raw. It should always be well cooked.

5. Unripe Foods.—Most vegetable foods are unfit to be eaten when green or unripe, especially if uncooked. Sometimes persons are made very sick indeed by eating such articles as green apples or unripe peaches.

6. Stale or Decayed Foods.—Food which has been allowed to stand until it is spoiled, or has become stale, musty, or mouldy, such as mouldy bread or fruit, or tainted meat, is unfit to be eaten, and is often a cause of very severe sickness. Canned fish or other meats spoil very quickly after the cans are opened, and should be eaten the same day.

7. Adulterated Foods.—Many of our foods are sometimes spoiled or injured by persons who put into them cheap substances which are harmful to health. They do this so as to make more money in selling them. This is called adulteration. The foods which are most likely to be injured by adulteration are milk, sugar, and butter.

8. Milk is most often adulterated by adding water, though sometimes other things are added.[Pg 16] Sometimes the water is not pure, and people are made sick and die. The adulteration of milk or any other food is a very wicked practice.

9. Butter is sometimes made almost wholly from lard or tallow. This is called oleomargarine or butterine. If the lard or tallow is from diseased animals, the false butter made from it may cause disease.

10. A great deal of the sugar and syrups which we buy is made from corn by a curious process, which changes the starch of the corn into sugar. Sugar which has been made in this way is not so sweet as cane sugar, and is not healthful.

11. Condiments or Seasonings.—These are substances which are added to our food for the purpose of giving to it special flavors. Condiments are not foods, because they do not nourish the body in any way, and are not necessary to preserve it in health.

12. The most common condiments are, mustard, pepper, pepper-sauce, ginger, cayenne-pepper, and spices. All these substances are irritating. If we put mustard upon the skin, it will make the skin red, and in a little time will raise a blister. If we happen to get a little pepper in the eye, it makes it smart and become very red and inflamed. When we take these [Pg 17]things into the stomach, they cause the stomach to smart, and its lining membrane becomes red just as the skin or the eye does.

13. Nature has put into our foods very nice flavors to make us enjoy eating them. Condiments are likely to do us great harm, and hence it is far better not to use them.

14. Tobacco.—Most of you know that tobacco is obtained from a plant which has long, broad leaves. These leaves are dried and then rolled up into cigars, ground into snuff, or prepared for chewing.

15. Tobacco has a smarting, sickening taste. Do you think it would be good to eat? Why not?

16. You know that tobacco makes people sick when they [Pg 18]first begin to use it. This is because it contains a very deadly poison, called nicotine.

17. If you give tobacco to a cat or a dog, it will become very sick. A boy once gave a piece of tobacco to a monkey, which swallowed it not knowing what a bad thing it was. The monkey soon became sick and died.

18. Many learned doctors have noticed the effects which come from using tobacco, and they all say it does great harm to boys, that it makes them puny and weak, and prevents their growing up into strong and useful men. If tobacco is not good for boys, do you think it can be good for men? Certainly you will say, No.

1. Both animals and plants are sometimes diseased. Flesh obtained from sick or diseased animals is unfit for food.

2. Unripe, stale, and mouldy foods are unfit to be eaten and likely to cause severe illness.

3. Foods are sometimes spoiled by having things mixed with them which are not food, or which are poisonous.

4. The foods most liable to be adulterated in this way are milk, sugar, and butter.

5. Tobacco, while not actually eaten, is thought by some persons to be a food, but it is not. It is a poison, and injures all who use it.

6. Boys who use tobacco do not grow strong in body and mind.

1. Water is really the only drink. It is the only substance which will satisfy thirst. All other fluids which we drink consist mostly of water. Thus, lemonade is lemon-juice and water. Milk is chiefly water. Wine, beer, cider, and such liquids contain alcohol and many other things, mixed with water.

2. Why we Need Water.—If we should wet a sponge and lay it away, it would become dry in a few hours, as the water would pass off into the air. Our bodies are losing water all the time, and we need to drink to keep ourselves from drying up.

3. Water is also very necessary for other purposes. It softens our food so that we can chew and swallow it, and helps to carry it around in the body after it has been digested, in a way about which we shall learn in future lessons.

4. Still another use for water is to dissolve and wash out of our bodies, through the sweat of the skin, and in other ways, the waste and worn-out particles which are no longer of any use.

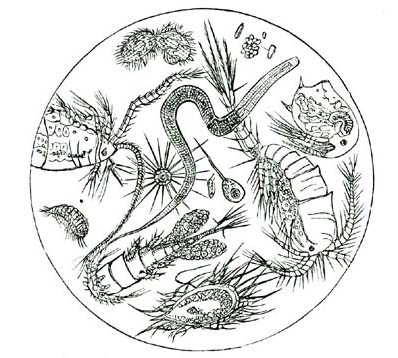

[Pg 20]5. Impure Water.—Most waters have more or less substances dissolved in them. Water which has much lime in it is called hard water. Such water is not so good to drink, or for use in cooking, as soft water. That water is best which holds no substances in solution. Well-water sometimes contains substances which soak into wells from vaults or cesspools. Slops which are poured upon the ground soak down out of sight; but the foul substances which they contain are not destroyed. They remain in the soil, and when the rains come, they are washed down into the well if it is near by. You can see some of the things found in bad water in the illustration given on opposite page.

6. It is best not to drink iced water when the body is heated, or during meals. If it is necessary to drink very cold water, the bad effects may be avoided by sipping it very slowly.

7. Tea and Coffee.—Many people drink tea or coffee at their meals, and some persons think that these drinks are useful foods; but they really have little or no value as foods. Both tea and coffee contain a poison which, when separated in a pure form, is so deadly that a very small quantity is enough to kill a cat or a dog. This poison often does much harm to those who drink tea or coffee very strong for any great length of time.

8. Alcohol (al´-co-hol).—All of you know something about alcohol. Perhaps you have seen it burn in a lamp. It will burn without a lamp, if we light it. It is so clear and colorless that it looks like water. The Indians call it "fire-water." Alcohol differs very much from foods. It is not produced from plants, as fruits and grains are; neither is it supplied by Nature ready for our use, as are air and water.

9. Fermentation.—When a baker makes bread he puts some yeast in the dough to make it "rise," so the bread will be light. The yeast [Pg 22]destroys some of the sugar and starch in the flour and changes it into alcohol and a gas. The gas bubbles up through the dough, and this is what makes the bread light. This is called fermentation (fer-men-ta´-tion). The little alcohol which is formed in the bread does no harm, because it is all driven off by the heat when the bread is baked.

10. Any moist substance or liquid which contains sugar will ferment if yeast is added to it, or if it is kept in a warm place. You know that canned fruit sometimes spoils. This is because it ferments. Fermentation is a sort of decay. When the juice of grapes, apples, or other fruit is allowed to stand in a warm place it "works," or ferments, and thus produces alcohol. Wine is fermented grape-juice; hard cider is fermented apple-juice.

11. Beer, ale, and similar drinks are made from grains. The grain is first moistened and allowed to sprout. In sprouting, the starch of the grain is changed to sugar. The grain is next dried and ground, and is then boiled with water. The water dissolves the sugar. The sweet liquid [Pg 23]thus obtained is separated from the grain, and yeast is added to it. This causes it to ferment, which changes the sugar to alcohol. Thus we see that the grain does not contain alcohol in the first place, but that it is produced by fermentation.

12. All fermented liquids contain more or less alcohol, mixed with water and a good many other things. Rum, brandy, gin, whiskey, and pure alcohol are made by separating the alcohol from the other substances. This is done by means of a still, and is called distillation.

13. You can learn how a still separates the alcohol by a little experiment. When a tea-pot is boiling on the stove and the steam is coming out at the nozzle, hold up to the nozzle a common drinking-glass filled with iced water, first taking care to wipe the outside of the glass perfectly dry. Little drops of water will soon gather upon the side of the glass. If you touch these to the tongue you will ob[Pg 24]serve that they taste of the tea. It is because a little of the tea has escaped with the steam and condensed upon the glass. This is distillation.

14. If the tea-pot had contained wine, or beer, or hard cider, the distilled water would have contained alcohol instead of tea. By distilling the liquid several times the alcohol may be obtained almost pure.

15. Alcohol kills Animals and Plants.—Strong alcohol has a deadly effect upon all living things. Once a man gave a dog a few tablespoonfuls of alcohol, and in a little while the dog was dead. If you should pour alcohol upon a plant it would die very soon.

16. A man once made a cruel experiment. He put some minnows into a jar of water and then poured in a few teaspoonfuls of alcohol. The minnows tried very hard to get out, but they could not, and in a little while they were all dead, poisoned by the alcohol. A Frenchman once gave alcohol to some pigs with their food. They soon became sick and died.

17. Alcohol not a Food.—There are some people who imagine that alcohol is good for food because it is made from fruits and grains which are good for food. This is a serious mistake. A person can live on the fruits or grains from [Pg 25]which alcohol is made, but no one would attempt to live upon alcohol. If he did, he would soon starve to death. In fact, men have often died in consequence of trying to use whiskey in place of food.

18. We should remember, also, that people do not take alcohol as a food, but for certain effects which it produces, which are not those of a food, but of a poison.

19. Many people who would not drink strong or distilled liquors, think that they will suffer no harm if they use only wine, beer, or cider. This is a great mistake. These liquids contain alcohol, as do all fermented drinks. A person will become drunk or intoxicated by drinking wine, beer, or cider—only a larger quantity is required to produce the same effect as rum or whiskey.

20. Another very serious thing to be thought of is that if a person forms the habit of drinking wine, cider, or other fermented drinks, he becomes so fond of the effect they produce that he soon wants some stronger drink, and thus he is led to use whiskey or other strong liquors. On this account it is not safe to use any kind of alcoholic drinks, either fermented or distilled. The only safe plan is to avoid the use of every sort of stimulating or intoxicating drinks.

21. It has been found by observation that [Pg 26]those persons who use intoxicating drinks are not so healthy as those who do not use them, and, as a rule, they do not live so long.

22. This is found to be true not only of those who use whiskey and other strong liquors, but also of those who use fermented drinks, as wine and beer. Beer drinkers are much more likely to suffer from disease than those who are strictly temperate. It is often noticed by physicians that when a beer-drinker becomes sick or meets with an accident, he does not recover so readily as one who uses no kind of alcoholic drinks.

23. Alcoholic drinks not only make people unhealthy and shorten their lives, but they are also the cause of much poverty and crime and an untold amount of misery.

1. Water is the only thing that will satisfy thirst.

2. In going through our bodies, water washes out many impurities. We also need water to soften our food.

3. The purest water is the best. Impure water causes sickness.

4. Good water has no color, taste, or odor.

5. Tea and coffee are not good drinks. They are very injurious to children, and often do older persons much harm.

6. Alcohol is made by fermentation.

7. Pure alcohol and strong liquors are made by distillation.

8. Alcohol is not a food, it is a poison. It kills plants and animals, and is very injurious to human beings.

9. Even the moderate use of alcoholic drinks produces disease and shortens life.

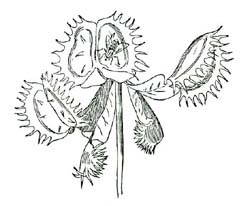

1. Did you ever see a Venus's fly-trap? This curious plant grows in North Carolina. It is called a fly-trap because it has on each of its leaves something like a steel-trap, by means of which it catches flies. You can see one of these traps in the picture. When a fly touches the leaf, the trap shuts up at once, and the poor fly is caught and cannot get away. The harder it tries to escape, the more tightly the trap closes upon it, until after a time it is crushed to death.

2. But we have yet to learn the most curious thing about this strange plant, which seems to act so much like an animal. If we open the leaf after a few days, it will be found that the fly has almost entirely disappeared. The fly has [Pg 28]not escaped, but it has been dissolved by a fluid formed inside of the trap, and the plant has absorbed a portion of the fly. In fact, it has really eaten it. The process by which food is dissolved and changed so that it can be absorbed and may nourish the body, is called digestion (di-ges´-tion).

3. The Venus's fly-trap has a very simple way of digesting its food. Its remarkable little trap serves it as a mouth to catch and hold its food, and as a stomach to digest it. The arrangement by which our food is digested is much less simple than this. Let us study the different parts by which this wonderful work is done.

4. The Digestive Tube.—The most important part of the work of digesting our food is done in a long tube within the body, called the digestive tube or canal.

5. This tube is twenty-five or thirty feet long in a full-grown man; but it is so coiled up and folded away [Pg 29]that it occupies but little space. It begins at the mouth, and ends at the lower part of the trunk. The greater part of it is coiled up in the abdomen.

6. The Mouth.—The space between the upper and the lower jaw is called

the mouth. The lips form the front part and the cheeks the sides. At

the back part are three openings. One, the upper, leads into the nose.

There are two lower openings. One of these leads into the stomach, and

the other leads to the lungs. The back part of the mouth joins the two

tubes which lead from the mouth to the lungs and the stomach, and is

called the throat. The mouth contains the tongue and the teeth.

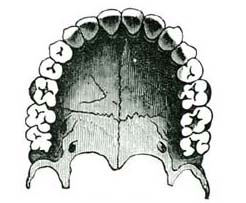

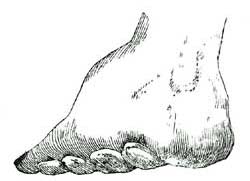

7. The Teeth.—The first teeth, those which come when we are small children, are called[Pg 30] temporary or milk teeth. We lose these teeth as the jaws get larger and the second or permanent teeth take their place. There are twenty teeth in the first set, and thirty-two in the second. Very old persons sometimes have a third set of teeth.

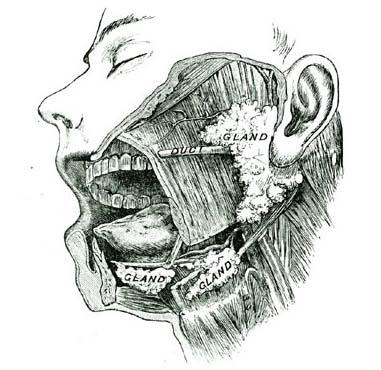

8. The Salivary (sal´-i-vary) Glands.—There are three pairs of salivary glands. They form a fluid called the saliva (sa-li´-va). It is this fluid which moistens the mouth at all times. When we eat or taste something which we like, the salivary glands make so much saliva that we some[Pg 31]times say the mouth waters. One pair of the salivary glands is at the back part of the lower jaw, in front of the ears. The other two pairs of glands are placed at the under side of the mouth. The saliva produced by the salivary glands is sent into the mouth through little tubes called ducts.

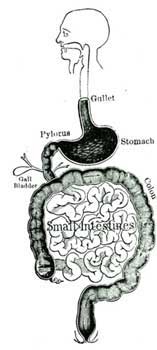

9. The Gullet.—At the back part of the throat begins a narrow tube, which passes down to the stomach. This tube is about nine inches long. It is called the gullet, food-pipe, or œsophagus (e-soph´-a-gus).

10. The Stomach.—At the lower end of the œsophagus the digestive tube becomes enlarged, and has a shape somewhat like a pear. This is the stomach. In a full-grown person the stomach is sufficiently large to hold about three pints. At each end of the stomach is a narrow opening so arranged that it can be opened or tightly closed, as may be necessary. The upper opening allows the food to pass into the stomach, the lower one allows it to pass out into the intestines. This opening is called the pylorus (py-lo´-rus), or gate-keeper, because it closes so as to keep the food in the stomach until it is ready to pass out.

11. In the membrane which lines the stomach there are many little pocket-like glands, [Pg 32]in which a fluid called the gastric juice is formed. This fluid is one of the most important of all the fluids formed in the digestive canal.

12. The Intestine(in-tes´-tine).—At the lower end of the stomach the digestive canal becomes narrow again. This narrow portion, called the intestine, is about twenty-five feet long in a grown person. The last few feet of the intestine is larger than the rest, and is called the colon. This long tube is coiled up and snugly packed away in the cavity of the abdomen. In the membrane lining the intestines are to be found little glands, which make a fluid called intestinal juice.

13. The Liver.—Close up under the ribs, on the right side of the body, is a large chocolate-colored organ, called the liver. The liver is about half as large as the head, and is shaped so as to fit snugly into its corner of the abdomen. The chief business of the liver is to make a fluid called bile, which is very necessary for the digestion of our food.

14. The bile is a bitter fluid of a golden-brown color. It is carried to the intestine by means of a little tube or duct, which enters the small in[Pg 33]testine a few inches below the stomach. When the bile is made faster than it is needed for immediate use, it is stored up in a little pear-shaped sac called the gall-bladder, which hangs from the under side of the liver.

15. The liver is a very wonderful organ, and does many useful things besides making bile. It aids in various ways in digesting the food, and helps to keep the blood pure by removing from it harmful substances which are formed within the body.

16. The Pancreas(pan´-cre-as).—The pancreas is another large and very important gland which is found close to the stomach, lying just behind it in the abdominal cavity. The pancreas forms a fluid called the pancreatic juice, which enters the small intestine at nearly the same place as the bile.

17. The Spleen.—Close to the pancreas, at the left side of the body, is a dark, roundish organ about the size of the fist, called the spleen. It is not known that the spleen has much to do in the work of digestion, but it is so closely connected with the digestive organs that we need to know about it.

18. Please note that there are five important organs of digestion. The mouth, the stomach, the intestines, the pancreas, and the liver.

[Pg 34]19. Also observe that there are five digestive fluids, saliva, gastric juice, bile, pancreatic juice, and intestinal juice.

1. The process of dissolving and changing the food so that it may be absorbed and may nourish the body is digestion.

2. The work of digestion is chiefly done in the digestive tube or canal, which is about thirty feet in length.

3. The mouth contains the teeth, and has three pairs of salivary glands connected with it, which make saliva.

4. The gullet leads from the mouth to the stomach.

5. The stomach is pear-shaped, and holds about three pints.

6. It has an upper and a lower opening, each of which is guarded by a muscle, which keeps its contents from escaping.

7. The lower opening of the stomach is called the pylorus.

8. The stomach forms the gastric juice.

9. The intestines are about twenty-five feet long. They form the intestinal juice.

10. The liver lies under the ribs of the right side. It is about half as large as the head. It makes bile.

11. When not needed for immediate use, the bile is stored up in a sac called the gall-bladder.

12. The pancreas is a gland which lies just back of the stomach. It makes pancreatic juice.

13. The spleen is found near the pancreas.

14. There are five important digestive organs—the mouth, the stomach, the intestines, the liver, and the pancreas.

15. There are five digestive fluids—saliva, gastric juice, intestinal juice, bile, and pancreatic juice.

1. Let us suppose that we have eaten a mouthful of bread, and can watch it as it goes through all the different processes of digestion.

2. Mastication.—First, we chew or masticate the food with the teeth. We use the tongue to move the food from one side of the mouth to the other, and to keep the food between the teeth.

3. Mouth Digestion.—While the bread is being chewed, the saliva is mixed with it and acts upon it. The saliva moistens and softens the food so that it can be easily swallowed and readily acted upon by the other digestive juices. You have noticed that if you chew a bit of hard bread a few minutes it becomes sweet. This is because the saliva changes some of the starch of the food into sugar.

4. After we have chewed the food, we swallow it, and it passes down through the œsophagus into the stomach.

5. Stomach Digestion.—As soon as the morsel of food enters the stomach, the gastric juice [Pg 36]begins to flow out of the little glands in which it is formed. This mingles with the food and digests another portion which the saliva has not acted upon. While this is being done, the stomach keeps working the food much as a baker kneads dough. This is done to mix the gastric juice with the food.

6. After an hour or two the stomach squeezes the food so hard that a little of it, which has been digested by the gastric juice and the saliva, escapes through the lower opening, the pylorus, of which we have already learned. As the action of the stomach continues, more of the digested food escapes, until all that has been properly acted upon has passed out.

7. Intestinal Digestion.—We sometimes eat butter with bread, or take some other form of fat in our food. This is not acted upon by the saliva or the gastric juice. When food passes out of the stomach into the small intestine, a large quantity of bile is at once poured upon it. This bile has been made beforehand by the liver and stored up in the gall-bladder. The bile helps to digest fats, which the saliva and the gastric juice cannot digest.

8. The pancreatic juice does the same kind of work that is done by the saliva, the gastric juice, and the bile. It also finishes up the work done [Pg 37]by these fluids. It is one of the most important of all the digestive juices.

9. The intestinal juice digests nearly all the different elements of the food, so that it is well fitted to complete the wonderful process by which the food is made ready to enter the blood and to nourish the body.

10. While the food is being acted upon by the bile, the pancreatic juice, and intestinal juice, it is gradually moved along the intestines. After all those portions of food which can be digested have been softened and dissolved, they are ready to be taken into the blood and distributed through the body.

11. Absorption.—If you put a dry sponge into water, it very soon becomes wet by soaking up the water. Indeed, if you only touch a corner of the sponge to the water, the whole sponge will soon become wet. We say that the sponge absorbs the water. It is in a somewhat similar way that the food is taken up or absorbed by the walls of the stomach and intestines. When the food is absorbed, the greater part of it is taken into the blood-vessels, of which we shall learn in a future lesson.

12. Liver Digestion.—After the food has been absorbed, the most of it is carried to the liver, where the process of digestion is completed. The [Pg 38]liver also acts like an inspector to examine the digested food and remove hurtful substances which may be taken with it, such as alcohol, mustard, pepper, and other irritating things.

13. The Thoracic Duct.—A portion of the food, especially the digested fats, is absorbed by a portion of the lymphatic vessels called lacteals, which empty into a small vessel called the thoracic duct. This duct passes upward in front of the spine and empties into a vein near the heart.

How a mouthful of food is digested:

1. It is first masticated—that is, it is chewed and moistened with saliva.

2. Then it is swallowed, passing through the œsophagus to the stomach.

3. There it is acted upon, and a part of it digested by the gastric juice.

4. It is then passed into the small intestine, where it is acted upon by the bile, the pancreatic fluid, and the intestinal juice.

5. The digested food is then absorbed by the walls of the stomach and intestines.

6. The greater portion of the food is next passed through the liver, where hurtful substances are removed.

7. A smaller portion is carried through the thoracic duct and emptied into a vein near the heart.

1. Eating too Fast.—A most common fault is eating too fast. When the food is chewed too rapidly, and swallowed too quickly, it is not properly divided and softened. Such food cannot be easily acted upon by the various digestive juices.

2. Eating too Much.—A person who eats food too rapidly is also very likely to injure himself by eating too much. The digestive organs are able to do well only a certain amount of work. When too much food is eaten, none of it is digested as well as it should be. Food which is not well digested will not nourish the body.

3. Eating too Often—Many children make themselves sick by eating too often. It is very harmful to take lunches or to eat at other than the proper meal-times. The stomach needs time to rest, just as our legs and arms and the other parts of the body do. For the same reason, it is well for us to avoid eating late at [Pg 40]night. The stomach needs to sleep with the rest of the body. If one goes to bed with the stomach full of food, the stomach cannot rest, and the work of digestion will go on so slowly that the sleep will likely be disturbed. Such sleep is not refreshing.

4. If we wish to keep our digestive organs in good order, we must take care to eat at regular hours. We ought not to eat when we are very tired. The stomach cannot digest well when we are very much fatigued.

5. Sweet Foods.—We ought not to eat too much sugar or sweet foods, as they are likely to sour or ferment in the stomach, and so make us sick. Candies often contain a great many things which are not good for us, and which may make us sick. The colors used in candies are sometimes poisonous. The flavors used in them are also sometimes very harmful.

6. Fatty Foods Hurtful.—Too much butter, fat meats, and other greasy foods are hurtful. Cream is the most digestible form of fat, because it readily dissolves in the fluids of the stomach, and mixes with the other foods without preventing their digestion. Melted fats are especially harmful. Cheese, fried foods, and rich pastry are very poor foods, and likely to cause sickness.

[Pg 41]7. Eating too many Kinds of Foods.—Children should avoid eating freely of flesh meats. They ought also to avoid eating all highly-seasoned dishes, and taking too many kinds of food at a meal. A simple diet is much the more healthful. Milk and grain foods, as oatmeal, cracked wheat, graham bread, with such delicious fruits as apples, pears, and grapes, are much the best food for children.

8. Avoid Use of Cold Foods.—We ought not to take very cold foods or liquids with our meals. Cold foods, ice-water, and other iced drinks make the stomach so cold that it cannot digest the food. For this reason it is very harmful to drink iced water or iced tea, or to eat ice-cream at meals. These things are injurious to us at any time, but they do the greatest amount of harm when taken with the food.

9. Things sometimes Eaten which are not Foods.—Things which are not foods are often used as foods, such as mustard, pepper, and the various kinds of seasonings. Soda, saleratus, and baking-powders also belong to this class. All of these substances are more or less harmful, particularly mustard, pepper, and hot sauces.

10. Common Salt.—The only apparent exception to the general rule that all condiments and other substances which are not foods are harm[Pg 42]ful is in the case of common salt. This is very commonly used among civilized nations, although there are many barbarous tribes that never taste it. It is quite certain that much more salt is used than is needed. When much salt is added to the food, the action of the digestive fluids is greatly hindered. Salt meats, and other foods which have much salt added to them, are hard to digest because the salt hardens the fibres of the meat, so that they are not easily dissolved by the digestive fluids.

11. Care of the Teeth.—The teeth are the first organs employed in the work of digestion. It is of great importance that they should be kept in health. Many persons neglect their teeth, and treat them so badly that they begin to decay at a very early age.

12. The mouth and teeth should be carefully cleansed immediately on rising in the morning, and after each meal. All particles of food should be removed from between the teeth by carefully rubbing both the inner and the outer surfaces of the teeth with a soft brush, and rinsing very thoroughly with water. A little soap may be used in cleansing the teeth, but clear water is sufficient, if used frequently and thoroughly. The teeth should not be used in breaking nuts or other hard substances. The teeth are brittle, [Pg 43]and are often broken in this way. The use of candy and too much sweet food is also likely to injure the teeth.

13. Some people think that it is not necessary to take care of the first set of teeth. This is a great mistake. If the first set are lost or are unhealthy, the second set will not be as perfect as they should be. It is plain that we should not neglect our teeth at any time of life.

14. Tobacco.—When a person first uses tobacco, it is apt to make him very sick at the stomach. After he has used tobacco a few times it does not make him sick, but it continues to do his stomach and other organs harm, and after a time may injure him very seriously. Smokers sometimes suffer from a horrible disease of the mouth or throat known as cancer.

15. Effects of Alcohol upon the Stomach.—If you should put a little alcohol into your eye, the eye would become very red. When men take strong liquors into their stomachs, the delicate membrane lining the stomach becomes red in the same way. Perhaps you will ask how do we know that alcohol has such an effect upon the stomach. More than sixty years ago there lived in Michigan a man named Alexis St. Martin. One day he was, by accident, shot in such a way that a large opening was made right [Pg 44]through the skin and flesh and into the stomach. The good doctor who attended him took such excellent care of him that he got well. But when he recovered, the hole in his stomach remained, so that the doctor could look in and see just what was going on. St. Martin sometimes drank whiskey, and when he did, the doctor often looked into his stomach to see what the effect was, and he noticed that the inside of the stomach looked very red and inflamed.

16. If St. Martin continued to drink whiskey for several days, the lining of the stomach looked very red and raw like a sore eye. A sore stomach cannot digest food well, and so the whole body becomes sick and weak. What would you think of a man who should keep his eyes always sore and inflamed and finally destroy his eyesight by putting pepper or alcohol or some other irritating substance into them every day? Is it not equally foolish and wicked to injure the stomach and destroy one's digestion by the use of alcoholic drinks? Alcohol, even when it is not very strong, not only hurts the lining of the stomach, but injures the gastric juice, so that it cannot digest the food well.

17. Effects of Alcohol upon the Liver.—The liver, as well as the stomach, is greatly damaged by the use of alcohol. You will recollect that [Pg 45]nearly all the food digested and absorbed is filtered through the liver before it goes to the heart to be distributed to the rest of the body. In trying to save the rest of the body from the bad effects of alcohol, the liver is badly burned by the fiery liquid, and sometimes becomes so shrivelled up that it can no longer produce bile and perform its other duties. Even beer, ale, and wine, which do not contain so much alcohol as do rum, gin, and whiskey, have enough of the poison in them to do the liver a great deal of harm, and to injure many other organs of the body as well.

| { | |||

| Eating too fast. | |||

| Eating too much. | |||

| Eating too frequently. | |||

| Eating irregularly. | |||

| 1. | Causes of Indigestion. | Eating when tired. | |

| Eating too much of sweet foods. | |||

| Eating too many kinds of food at a meal. | |||

| Using iced foods or drinks. |

2. Irritating substances and things which are not foods should not be eaten.

3. The teeth must be carefully used and kept clean.

4. Tobacco-using does the stomach harm, and sometimes causes cancer of the mouth.

5. Alcohol injures the gastric juice, and causes disease of the stomach and the liver.

1. The Blood.—Did you ever cut or prick your finger so as to make it bleed? Probably you have more than once met with an accident of this sort. All parts of the body contain blood. If the skin is broken in any place the blood flows out.

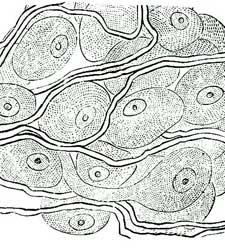

2. How many of you know what a microscope is? It is an instrument which magnifies objects, or makes them look a great deal larger than they really are. Some microscopes are so powerful that they will make a little speck of dust look as large as a great rock.

3. The Blood Corpuscles.—If you should look at a tiny drop of blood through such a microscope, you would find it to be full of very small, round objects called blood corpuscles.

4. You would notice also that these corpuscles are of two kinds. Most of them are slightly reddish, and give to the blood its red color. A very few are white.

5. Use of the Corpuscles.—Do you wonder what these peculiar little corpuscles do in the [Pg 47]body? They are very necessary. We could not live a moment without them. We need to take into our bodies oxygen from the air. It is the business of the red corpuscles to take up the oxygen in the lungs and carry it round through the body in a wonderful way, of which we shall learn more in a future lesson.

6. The white corpuscles have something to do with keeping the body in good repair. They are carried by the blood into all parts of the body and stop where they are needed to do any kind of work. They may be compared to the men who go around to mend old umbrellas, and to do other kinds of tinkering. It is thought that the white corpuscles turn into red ones when they become old.

7. The corpuscles float in a clear, almost colorless fluid which contains the digested food and other elements by which the body is nourished.

1. The blood contains very small objects called blood corpuscles.

2. There are two kinds of corpuscles, red and white.

3. The red corpuscles carry oxygen.

4. The white corpuscles repair parts that are worn.

5. The corpuscles float in a clear, almost colorless fluid, which nourishes the body.

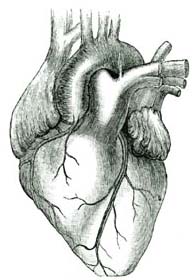

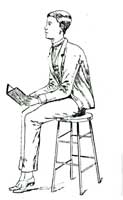

1. If you place your hand on the left side of your chest, you will feel something beating. If you cannot feel the beats easily, you may run up and down stairs two or three times, and then you can feel them very distinctly. How many of you know the name of this curious machine inside the chest, that beats so steadily? You say at once that it is the heart.

2. The Heart.—The heart may be called a live pump, which keeps pumping away during our whole lives. If it should stop, even [Pg 49]for a minute or two, we would die. If you will place your hand over your heart and count the beats for exactly one minute, you will find that it beats about seventy-five or eighty times. When you are older, your heart will beat a little more slowly. If you count the beats while you are lying down, you will find that the heart beats more slowly than when you are sitting or standing. When we run or jump, the heart beats much harder and faster.

3. Why the Heart Beats.—We have learned in preceding lessons that the digested food is taken into the blood. We have also learned that both water and oxygen are taken into the blood. Thus the blood contains all the materials that are needed by the various parts of the body to make good the wastes that are constantly taking place. But if the blood were all in one place it could do little good, as the new materials are needed in every part of the body. There has been provided a wonderful system of tubes running through every part of the body. By means of these tubes the blood is carried into every part where it is required. These tubes are connected with the heart. When the heart beats, it forces the blood through the tubes just as water is forced through a pipe by a pump or by a fire-engine.

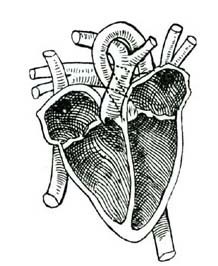

[Pg 50]4. The Heart Chambers.—The heart has four chambers, two upper and two lower chambers. The blood is received into the upper chambers, and is then passed down into the lower chambers. From the lower chambers it is sent out to various parts of the body.

5. The Blood-Vessels.—The tubes through which the blood is carried are called blood-vessels. There are three kinds of blood-vessels. One set carry the blood away from the heart, and are called arteries (ar'-te-ries). Another set return the blood to the heart, and are called veins. The arteries and veins are connected at the ends farthest from the heart by many very small vessels. These minute, hairlike vessels are called capillaries (cap'-il-la-ries).

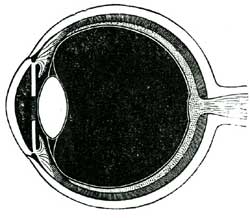

6. The Arteries.—An artery leads out from the lower chamber of each side of the heart. The one from the right side of the heart carries the blood only to the lungs. The one from the left side of the heart carries blood to every part of the body. It is the largest [Pg 51]artery in the body, and is called the aorta. Soon after it leaves the heart the aorta begins to send out branches to various organs. These divide in the tissues again and again until they become so small that only one corpuscle can pass through at a time, as shown in the colored plate. (Frontispiece.)

7. The Veins.—These very small vessels now begin to unite and form larger ones, the veins. The small veins join to form larger ones, until finally all are gathered into two large veins which empty into the upper chamber of the right side of the heart. The veins which carry blood from the lungs to the heart empty into the upper chamber of the left side of the heart.

8. What is Done in the Blood-Vessels.—While the blood is passing through the small blood-vessels in the various parts of the body, each part takes out just what it needs to build up its own tissues. At the same time, the tissues give in exchange their worn-out or waste matters. The red blood corpuscles in the capillaries give up their oxygen, and the blood receives in its stead a poisonous substance called carbonic-acid gas.

9. Red and Blue Blood.—While in the arteries the blood is of a bright red color; but while it is passing through the capillaries the color [Pg 52]changes to a bluish red or purple color. The red blood is called arterial blood, because it is found in the arteries. The purple blood is called venous blood, because it is found in the veins. The loss of oxygen in the corpuscles causes the change of color.

10. Change of Blood in the Lungs.—Exactly the opposite change occurs in the blood when it passes through the lungs. The blood which has been gathered up from the various parts of the body is dark, impure blood. In the lungs this dark blood is spread out in very minute capillaries and exposed to the air. While passing through the capillaries of the lungs, the blood gives up some of its impurities in exchange for oxygen from the air. The red corpuscles absorb the oxygen and the color of the blood changes from dark purple to bright red again. The purified blood is then carried back to the upper chamber of the left side of the heart through four large veins. The blood is now ready to begin another journey around the body.

11. The Pulse.—If you place your finger on your wrist at just the right spot, you can feel a slight beating. This beating is called the pulse. It is caused by the movement of the blood in the artery of the wrist at each beat of the heart. The pulse can be felt at the neck and in other [Pg 53]parts of the body where an artery comes near to the surface.

12. How much Work the Heart Does.—The heart is a small organ, only about as large as your fist, and yet it does an amount of work which is almost beyond belief. Each time it beats, it does as much work as your arm would do in lifting a large apple from the ground to your mouth. It beats when we are asleep as well as when we are awake. When we run we know by the way in which it beats that it is working very fast. Do you know how much a ton is? Well, in twenty-four hours the heart does as much work as a man would do in lifting stones enough to weigh more than one hundred and twenty tons.

13. The Lymphatics.—While the blood is passing through the capillaries, some of the white corpuscles escape from the blood-vessels. What do you suppose becomes of these runaway corpuscles? Nature has provided a way by which they can get back to the heart. In the little spaces among the tissues outside of the blood-vessels very minute channels called lymph channels or lymphatics (lym—phat'-ics) begin. The whole body is filled with these small channels, which run together much like the meshes of a net. In the centre of the body the small lymphatics run into large ones, which empty into [Pg 54]the veins near the heart. This is the way the stray white blood corpuscles get back into the blood.

14. The Lymph.—In the lymph channels the white corpuscles float in a colorless fluid called lymph. The lymph is composed of the fluid portion of the blood which has soaked through the walls of the small vessels. The chief purpose of the lymphatics is to carry the lymph from the tissues back to the heart.

15. Lymphatic Glands.—Here and there, scattered through the body, are oval structures into each of which many lymphatic vessels are found to run, as shown in the illustration. These are called lymphatic glands.

16. The heart and blood-vessels are among the most wonderful

structures in the body. It is no wonder, then, that alcohol, tobacco,

and other narcotics and stimulants produce their most deadly effects

upon these delicate organs. What these effects are we shall learn more

fully in the next chapter.

1. The heart beats to circulate the blood.

2. The heart has four chambers, two upper and two lower.

3. There are tubes called blood-vessels which carry the blood to all parts of the body.

4. These tubes are connected with the heart.

5. The vessels which carry blood away from the heart are called arteries, and those which carry blood back to the heart are called veins.

6. The arteries and veins are connected by small tubes called capillaries.

7. The blood found in the arteries is red; that in the veins is dark blue or purple.

8. The color of the blood changes from red to blue in going through the capillaries. The change is due to the loss of oxygen.

9. In the circulation of the lungs, the blood in the arteries is blue, that in the veins, red.

10. The change from blue to red takes place while the blood is passing through the capillaries of the lungs. The change is due to the oxygen which the corpuscles of the blood take up in the lungs.

11. The pulse is caused by the beating of the heart.

12. The heart does a great deal of work every day in forcing the blood into different parts of the body.

13. Some of the white blood corpuscles escape from the blood-vessels through the thin walls of the capillaries.

14. These corpuscles return to the heart through small vessels called lymph channels or lymphatics.

15. The lymphatics in many parts of the body run into small roundish bodies called lymphatic glands.

16. The object of the lymphatics is to remove from the tissues and return to the general circulation the lymph and white blood corpuscles which escape through the walls of the capillaries.

1. The heart is one of the most important of all the organs of the body. If we take good care of it, it will do good service for us during a long life. Let us notice some ways in which the heart is likely to be injured.

2. Violent Exercise.—Did you ever run so hard that you were out of breath? Do you know why you had to breathe so fast? It was because the violent exercise made your heart beat so rapidly that the blood could not get out of the lungs as fast as the heart forced it in. The lungs became so filled with blood that they could not do their work well. Sometimes, when a person runs very fast or takes any kind of violent exercise, the lungs become so filled with blood that a blood-vessel is broken. The person may then bleed to death. It is very unwise to overtax the heart in any way, for it may be strained or otherwise injured, so that it can never again do its work properly.

[Pg 57]3. Effects of Bad Air.—Bad air is very harmful to the heart and to the blood also. We should always remember that the blood of the body while passing through the lungs is exposed to the air which we breathe. If the air is impure, the blood will be poisoned. In churches and in other places where the air becomes foul, people often faint from the effects of the impure air upon the heart. It is important that the air of the rooms in which we live and sleep should be kept very pure by good ventilation.

4. Effects of Bad Food.—The blood is made from what we eat, and if we eat impure and unwholesome food, the blood becomes impure. We ought to avoid the use of rich or highly-seasoned foods, candies, and all foods which are not nutritious. They not only injure the blood by making it impure, but they cause poor digestion.

5. Plenty of Sleep Necessary.—If we should take a drop of blood from the finger of a person who had not had as much sleep as he needed, and examine it with a microscope, we should find that there were too few of the little red-blood corpuscles. This is one reason why a person who has not had sufficient sleep looks pale.

6. Proper Clothing.—We should be properly clothed, according to the weather. In cold [Pg 58]weather we need very warm clothing. In warm weather we should wear lighter clothing. Our clothing should be so arranged that it will keep all parts of the body equally warm, and thus allow the blood to circulate properly. The feet are apt to be cold, being so far away from the heart, and we should take extra pains to keep them warm and dry.

7. Effects of Excessive Heat.—In very hot weather, many persons are injured by exposing themselves to the sun too long at a time. Persons who drink intoxicating liquors are very often injured in this way, and sometimes die of sunstroke.

8. Effects of Anger.—When a person gets very angry, the heart sometimes almost stops beating. Indeed, persons have died instantly in a fit of passion. So you see it is dangerous for a person to allow himself to become very angry.

9. Effects of Alcohol upon the Blood.—If you should take a drop of blood upon your finger, and put it under the microscope, and then add a little alcohol to it, you would see that the corpuscles would be quickly destroyed. In a few seconds they would be so shrivelled up that no one could tell that they had ever been the beautiful little corpuscles which are so necessary to health. When alcohol is taken as a drink, it does not de[Pg 59]stroy the corpuscles so quickly, but it injures them so that they are not able to do their work of absorbing and carrying oxygen well. This is one reason why the faces of men who use alcoholic drinks often look so blue.

10. Alcohol Overworks the Heart.—Dr. Parkes, a very learned English physician, took the pains to observe carefully the effects of alcohol upon the heart of a soldier who was addicted to the use of liquor. He counted the beats of the soldier's pulse when he was sober; and then counted them again when he was using alcohol, and found that when the soldier took a pint of gin a day his heart was obliged to do one fourth more work than it ought to do.

11. Effects of Alcohol upon the Blood-Vessels.—If you put your hands into warm water, they soon become red. This is because the blood-vessels of the skin become enlarged by the heat, so that they hold more blood. Alcohol causes the blood to come to the surface in the same way. It is this that causes the flushed cheeks and the red eyes of the drunkard. Sometimes, after a man has been using alcohol a long time, the blood-vessels of his face remain enlarged all the time. This makes his nose grow too fast, and so in time it gets too large, and then he has a rum-blossom.

[Pg 60]12. Effects of Tobacco on the Heart and the Blood.—When a boy first tries to use tobacco, it makes him feel very sick. If you should feel his pulse just then, you would find it very weak. This means that the heart is almost paralyzed by the powerful poison of the tobacco. Tobacco also injures the blood corpuscles.

13. Tea and coffee also do their share of mischief to the heart. Those who use them very strong often complain of palpitation, or heavy and irregular beating of the heart.

14. Taking Cold.—People usually "catch cold" by allowing the circulation to become disturbed in some way, as by getting the feet wet, being chilled from not wearing sufficient clothing, sitting in a draught, and in other similar ways. It is very important for you to know that a cold is a serious thing, and should be carefully avoided.

15. Hemorrhage (hem'-or-rhage) or Loss of Blood.—A severe loss of blood is likely to occur as the result of accidents or injuries of various sorts, and it is important to know what to do at once, as there may not be time to send for a doctor before it will be too late to save the injured person's life. Here are a few things to be remembered in all such cases:

16. If the blood from a cut or other wound [Pg 61]flows in spurts, and is of a bright red color, it is from an artery. If it is dark-colored, and flows in a steady stream, it is from a vein.

17. How to Stop the Bleeding of Wounds.—If the bleeding vessel is an artery, apply pressure on the side of the wound next to the heart. If the bleeding is from a vein, apply it on the opposite side. It is generally best to apply pressure directly over the wound or on both sides. The pressure can be made with the thumbs or with the whole hand. Grasp the part firmly and press very hard, or tie a handkerchief or towel around the wounded part and twist it very tight. If an arm or limb is the part injured, the person should be made to lie down, and the injured part should be held up. This is of itself an excellent means of stopping hemorrhage.

18. Nose-Bleed.—For nose-bleed a very good remedy is holding one or both hands above the head. The head should be held up instead of being bent forward, and the corner of a dry handkerchief should be pressed into the bleeding nostril. It is well to bathe the face with very hot water, and to snuff hot water into the nostril if the bleeding is very severe. If the bleeding is very bad or is not readily stopped, a physician should be called.

1. Violent exercise is likely to injure the heart.

2. Bad air makes the blood impure and disturbs the action of the heart.

3. Unwholesome food produces bad blood.

4. Too little sleep makes the blood poor.

5. Proper clothing is necessary to make the blood circulate equally in different parts of the body.

6. Violent anger may cause death by stopping the beating of the heart.

7. Alcohol injures the blood.

8. Alcohol overworks the heart.

9. Alcohol enlarges the blood-vessels.

10. Tobacco injures the blood.

11. Tobacco weakens the heart and makes the pulse irregular.

12. The use of strong tea and coffee causes palpitation of the heart.

13. A cold is caused by a disturbance of the circulation. A cold should never be neglected.

14. When an artery is wounded, the blood is bright red and flows in spurts.

15. When a vein is wounded, the blood is purple and flows in a steady stream.

16. To stop bleeding from an artery, press on the side of the wound towards the heart, or on both sides of the wound.

17. When a vein is wounded, press on the side away from the heart.

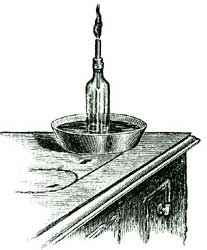

1. An Experiment.—Let us perform a little experiment. We must have a small bit of candle, a fruit jar, or a bottle with a large mouth, and a piece of wire about a foot long. Let us notice carefully what we are about to do and what happens.

2. We will fasten the candle to the end of the wire. Now we will light it, and next we will let it down to the bottom of the jar. Now place the cover on the top of the jar and wait the results. Soon the candle burns dimly and in a little time the light goes out altogether.

3. What do you think is the reason that the candle will not burn when shut up in a bottle? A candle uses air when it burns. If shut up in a small, tight place, it soon uses up so much air that it can burn no longer. Try the experiment again, and when the candle begins to burn dimly, take it out quickly. We see that at once the light burns bright again.

4. Suppose we shut the stove draught tight, [Pg 64]what is the result? The fire will burn low, and after a time it will probably go out. Why is this? Evidently the stove needs air to make the wood or coal burn, just as the candle needs air to make it burn.

5. Animals Die without Air.—If you should shut up a mouse or any other small animal in a fruit-jar, its life would go out just as the light of the candle went out. The little animal would die in a short time. A child shut up in a close place would die from the same cause in a very little time. In fact, many children are dying every day for want of a sufficient supply of pure air.

6. Oxygen.—The reason why animals need air, and why the fire will not burn without it, is that the air contains oxygen, and it is the oxygen of the air which burns the wood or coal and produces heat. So it is the oxygen that burns in our bodies and keeps us warm.

7. When wood and coal are burned, heat is produced; but some parts of the fuel are not made into heat. While the fire burns, smoke escapes through the pipe or chimney; but a part of the fuel remains in the stove in the form of ashes. Smoke and ashes are the waste parts of the fuel.

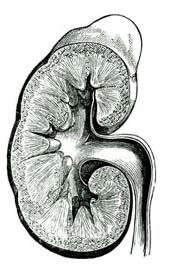

8. Poison in the Breath.—The burning which takes place in our bodies produces something [Pg 65]similar to the smoke and ashes produced by the fire in a stove. The smoke is called carbonic-acid gas,[A] an invisible vapor, and escapes through the lungs. The ashes are various waste and poisonous matters which are formed in all parts of the body. These waste matters are carried out of the body through the skin, the kidneys, the liver, and other organs.

9. Another Experiment.—We cannot see the gas escape from our lungs, but we can make an experiment which will show us that it really does pass out. Get two drinking-glasses and a tube. A glass tube is best, but a straw will do very well. Put a little pure water into one glass and the same quantity of lime-water into the other glass. Now put one end of the tube into the mouth and place the other end in the pure water. Breathe through the tube a few times. Look at the water in the glass and see that no change has taken place. Now breathe through the lime-water in the same way. After breathing two or three times, you will notice that the lime-water begins to look milky. In a short time it becomes almost as white as milk. This is because the lime-water catches the carbonic-acid gas which escapes from our lungs with each breath, while the pure water does not.

[Pg 66]10. Why we Breathe.—By this experiment we learn another reason why we breathe. We must breathe to get rid of the carbonic-acid gas, which is brought to the lungs by the blood to be exchanged for oxygen. There are two reasons then why we breathe: (a) to obtain oxygen; (b) to get rid of carbonic-acid gas.

11. How a Frog Breathes.—Did you ever see a frog breathe? If not, improve the first opportunity to do so. You will see that the frog has a very curious way of breathing. He comes to the top of the water, puts his nose out a little, and then drinks the air. You can watch his throat and see him swallowing the air, a mouthful at a time, just as you would drink water.

12. If you had a chance to see the inside of a frog you would find there a queer-shaped bag. This is his air-bag. This bag has a tube running up to the throat. When the frog comes to the surface of the water he fills this bag with air. Then he can dive down into the mud out of sight until he has used up the supply of air. When the air has been changed to carbonic-acid gas, he must come to the surface to empty his air-bag and drink it full again.