IN MEDIO TUTISSIMUS!

"What! Never been Ill since you were born! I suppose you're a Teetotaller?"

"Oh no! Been a Moderate Drunkard all my life!"

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 109, August 24, 1895, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 109, August 24, 1895 Author: Various Editor: Francis Burnand Release Date: September 18, 2014 [EBook #46895] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Lesley Halamek and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

"What! Never been Ill since you were born! I suppose you're a Teetotaller?"

"Oh no! Been a Moderate Drunkard all my life!"

The Irish Yolk.—In the name of the Profit—eggs! Irish co-operators have already made giant strides in the production of milk and butter, and now the Irish Co-operative Agency has decided, so says the Cork Daily Herald, to "take up the egg-trade." We hope the egg-traders won't be "taken up," too; if so, the trade would be arrested just when it was starting, and where would the profit be then? "It is stated that many Irish eggs now reach the English market dirty, stale, and unsorted," so that wholesale English egg-merchants have preferred to buy Austrian and French ones. Ireland not able to compete with the foreigner! Perish the thought! A little technical education judiciously applied will soon teach the Irish fowl not to lay "shop 'uns."

"The railway race to the North, like the race across the Atlantic, has placed beyond challenge that on land as well as on sea Scotch engines break the record."—North British Daily Mail.

Did not Lord Byron anticipate this when he wrote (in Mr. Punch's version of his poem on "Dark Lochnagar"):—

Yes, Caledonia, thy engines are scrumptious,

Though even in England some good ones are seen;

And, if the confession won't render you bumptious,

We sigh for your flyers to far Aberdeen!

But if Caledonia is inclined to boast about its locomotives, let it ponder its tinkers, and learn humility. The Glasgow "Departmental Committee on Habitual Offenders, Vagrants, &c.," reports that the nomad tinkers of Scotland number 1702, and of these 232 "were apprehended for some crime or other during the year." They don't do 151 miles in 167 minutes, like the locomotives—no, they do a couple of months in Glasgow gaol; and they break the laws instead of breaking records. There are 725 tinker children, who get practically no education. Bonnie Scotland, land of grandeur, where the thousand tinkers wander, you must catch these children, and educate them! The adult tinker may be irreclaimable, but at least the children should have a chance of something better—a choice of being soldier, sailor, tinker, or tailor, as they prefer. If, after all, they elect to tink, tink they must.

Dr. John Rhys, of Jesus College, Oxford, quite rose to the occasion at the New Quay, Eisteddfod, and, in his presidential address, made lengthy quotations in Welsh. "Na chaib a rhaw" must mean "nor cares a rap." By the way, the South Wales Daily News, in reporting the proceedings, finishes up by declaring that "the speech was listened to with 'wrapt' attention." As Mrs. Malaprop remarked, "The parcel was enraptured in brown paper."

Me and a werry old Frend of mine has seized the hoppertoonity that ardly ever okkers to too frends as has little or nothink to do for a hole week, to thurrowly enjoy theirselves for that time, and see weather sutten places in our little world is reelly as butiful and as injoyable as sum peeple tries to make out as they is. Our fust place was Epping Forrest, where we spent a hole day from morning to nite in what my frend called such a gallaxy of buty and wunder as werry likely werry few peeple ever has injoyd as we did. We spent hole miles among the most butiful Forest Trees as was ever seed, every single tree of which was rather more butiful than the last, and not one of which but what was a reel bootiful studdy. It took us jest about two hours to eat our dinner afore we set to work again to pollish off the lovely trees we had not yet seen; and then, when we had pollished off the last of them, we staggered to our werry last carridge, and took the sleep of the Just, and did not wake up till Brekfust come kindly to our assistance, and helped us to sett out and try again to dishcover similar seens of delishus injoyment to those so marwellusly injoyed the day before!

The trees as we xamined on the secund day was quite a diffrent class to them on the fust, and emused us every bit as delifefully as the fust sett, tho they was quite a diffrent sett altogether. In won place we drove bang into the wery middel of the thickest wood, and there we both lost ourselves for nearly three ours, but it wasn't a minnet too much for us, for we both agreed that, upon the hole, it was about the werry loveliest part of the hole day's proceedens, and that we shoud not regret havin to repeat it the next day. Oh them hundereds and thowsends of lovely Trees! every one of which seems far more butiful than the last, and quite equal to any we had yet seen. At one place we was showed the place where Good Quean Alizebeth always went up stairs on Orseback, coz she did not like going up stairs in public. At another we was showed where the present Queen sat in her privet Carridge, and made the hole nayberhood bow to her by the hunderd. Tom and Me both went up to the werry place, and pinted it out to them as didn't kno it, which made us both feel werry grand. The werry next day we had made all our derangements for follering up our prewius wisitashun, and making a grand fi-nayle of the hole lovely affare, when, to our tremenjus disapintment, the wind begun for to blow most orfully, and the rain begun for to rain wus as I beleeves, and as Tom beleeves, than ewer it did afore, and so we was both obleeged for to leeve our truly lovely forests, and defer our tree climing till a much more drier hoppertoonity, which we both bleeves will appear in about a week, and then we shall renew our grand old wisit as before, and lern again to beleeve in our hundereds and thowsends of the most buteful trees as ewen old hingland can brag about, as the most lovelyest as the world ewer saw.

And to think that all the lovely places as we seed in them three lovely days is past and gorn for the present, makes us long only the more artily for the glorius days still in store for us!

Sergeant-Major and Mrs. Baker were one of a trio of couples successful in winning their claim to the prize of a flitch of bacon at Dunmow. Three hundred and sixty-six days of married life without a flitch—we should say, hitch—in the flow of amicable intercourse is, nowadays, a marvellous achievement, and merits due recognition. We, however, commiserate the gallant and hambitions sergeant-major on having his matrimonial intentions aspersed by the opposing counsel, who, in attempting to "save the bacon," suggested that "Baker had one eye on the lady and the other eye on the flitch." The prospect of a reward even "more lasting than ham" would hardly, it is to be feared, serve to keep ordinary couples from "tiffs" for the space of a year and a day continuously.

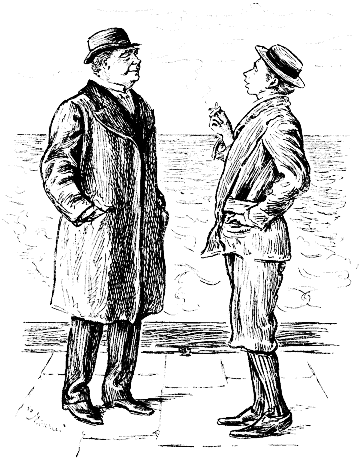

Father Thames. "Now then, stir up, old Stick-in-the-Mud! Summer or Winter, you're still found wanting, and then I get the blame!"

(Soliloquy of a Victorious Statesman.)

[Mr. Chamberlain at the opening of Parliament wore a red orchid in his buttonhole.]

Of colour-symbols much we hear,

And something, too, of colour-music;

But here's a sight that much I fear

Will make the beaten Red Rad crew sick:

Red! 'Tis the hue of my old flag—

In days that are as dead as mutton;

Now, with the instinct of a wag,

I sport it still,—but at my button.

It signifies how much I care

For the "consistency," quite brainless,

Which is the Radical bugbear.

Their poisoned darts are harmless, painless.

Judas? Egregious Tanner tries,

In vain, to link me with Iscariot.

What need I care for envious lies,

With S. and B. bound to my chariot.

They'd bite my heel, I crush their head,

And wear their colour in—my orchid!

Red! It will make the Rads "see red,"

They're fangless, though their tongues be forkèd.

"They toil not, neither do they spin,"—

I said, of the old Tory lilies.

Now they will have to work, to win,

And that the Rads don't see—the sillies!

Salisbury's Tories were one thing,

My Unionists are another matter;

My Ransom-Song no more I sing,—

Then I was bowler, now I'm batter.

We have new wickets, smooth and dry,

And one who coolly smites and places,

May, with firm wrist and steady eye,

Outshine the greatest of the Graces,

"The white flower of a blameless life"

Is—well, laid up at last at Harwarden,

Sheltered from storm, afar from strife,

And—other blossoms deck the garden.

Roses and lilies had their turn,

Now other blooms woo sun and showers;

And the Red Orchid—well, they'll learn—

In time—the new Language of Flowers!

Of parasitic opulence

Orchids are types, it will be said,

The difference though may be immense

When the new Orchid's mine—and Red!

Young Wife. "Oh, Mamma, do you know I believe Alfred's going to reform and give up Gambling!"

Her Mother. "What makes you think so dear?"

Young Wife. "Why all last night he kept talking in his sleep about his miserable, worthless Heart!"

(A School-Board Chronicle.)

"Utterly impossible!" replied the official. "A good plain cook! No, the Board does not create persons of that kind. If you had wanted a chef for a club, or a cordon bleu for a West End hotel, we might have accommodated you. But a good plain cook! No—utterly impossible!"

"But surely cookery is taught in the schools," pleaded the Ratepayer.

"Assuredly. And very well taught too. But whom would be satisfied with a mutton-chop? We aim at something higher. Our scholars are equal to producing sole à gratin, or suprême de volaille. And you don't require those plats every day of your life, now do you?"

"Then, can I have a housemaid?"

"I am afraid not. Since music has become one of the recognised branches of study, we do not obtain many candidates for the task of stair-sweeping. And it is not surprising. A girl who can play the piano, or lead a chorus, is surely worthy of a better fate than that which usually falls to the lot of a servant in a middle-class establishment."

"I suppose it is useless to ask you if you can give me the name of a boy in buttons?"

"Quite. To tell you the truth, we do not encourage such appointments. Our lads are wanted at their studies until they are growing too old to be young pages. Then, when they have reached the required standard their literary attainments entitle them to something superior to the post of a drudge in the pantry."

"Then what do you propose doing with your charges?" asked the Ratepayer, who was rapidly becoming resigned to his position.

"Well, our chefs must wait until the time arrives when there will be enough clubs and West End hotels to secure the benefit of their services."

"And the musicians?"

"They, too, at present are rather a drug in the market. But who knows? Some day there may be a huge demand for pianoforte players."

"And the literary lads?"

"Most admirably adapted for clerkships, but the clerical labour market is as dull as the proverbial ditchwater. Still, things may revive. But for the present they must hope and wait."

"And I provide the funds for all this?" cried the Ratepayer.

"You do," returned the official promptly. "This year it will be elevenpence halfpenny in the pound, and next probably considerably higher. But then you see—it is quite worth the money!"

(By Our Own Enterprising Explorer.)

"Why not go to Amsterdam?" At first sight this conundrum had the customary couple of answers, "No time, no money." But these were incorrect solutions.

"My dear Sir," said the Secretary of a Society organised to bring happiness into the humblest home (pronunciation with or without aspirates, according to the taste of the speaker), taking me up smartly, "you can get there in less than no time, remain there less than no time, and be back in less than no time. We can manage that for you."

"But the expense?"

"We should not be a Society organised to bring happiness into the humblest home if we could not manage that also. Look here: start Day 1 at 6.30 P.M.; be in Amsterdam morning of Day 2. Pause of thirty-six hours for refreshment; then back again to London in time for breakfast on Day 4. And with a view to bringing happiness into the humblest home we charge a guinea for travelling expenses, which includes a state cabin in the saloon of an excellent boat."

So I closed with the Secretary, and brought away happiness to my humble home. On the whole that happiness was maintained. It is true that the excellent boat was rather leisurely in her movements. I went to the Hook of Holland in a gale, which was kind enough to wait for my return off the Dutch coast, and accompany me back to the white cliffs of Albion. The excellent boat seemed to be on quite friendly terms with this gale, and to enjoy its company. Instead of flying from shore to shore, after the fashion of other steamers, the excellent boat toyed with each wave, lingered languidly amongst every billow, and arrived at her destination, both coming and going, several hours late. She appeared during the voyages to keenly appreciate a characteristic movement in sea. That characteristic movement in sea produced more gravity than gaiety amongst the passengers. Leaving the excellent boat out of the question—which boat, by the way, would no doubt have been more than excellent minus the gale—the journey "there and back" was accomplished with comfort and despatch.

On my arrival at Amsterdam I found myself in a city that, in its main characteristics, was not entirely unlike Brixton. The shops and the people were both suggestive of the southern suburb. The trams that, according to the guide-books, "traversed the town in every direction," were also reminiscent of that delightful haven of rest (from Saturday to Monday) of the overworked stockbroker and the underworked Government employé.

"You are sure to like Amsterdam," a friend of mine had said, as he pressed my hand at parting, "because it's exactly like the Regent's Park Canal."

My friend was right. Amsterdam certainly resembles the Regent's Park Canal, but plus Brixton. No doubt it is for this reason that it is sometimes called "the Northern Venice." The people, too, had a suburban look about them. I felt sure that most of them were called Smith, Brown, Jones, and Robinson, with perhaps a conventional "dam" tacked on to the end of their names to show that by nationality they were Dutchmen. I approached one of these good, honest creatures, who looked like Smithdam, and in my best broken English asked for the Hotel Amstel. I pronounced the latter word as if the last syllable rhymed with "peal." Mr. Smithdam stared at me and shook his head. Then he said "Nine."

"'Otel Amstale," I continued, with a new pronunciation. "You know what mean I—'Otel Amstale?"

But Mr. Smithdam didn't. He smiled, and again shook his head. This annoyed me, so I murmured, "What an ass this chap must be; fancy not knowing the way to the Amstel Hotel!"

"Amstel Hotel," he cried, with a pronunciation infinitely more English than my own, and then most courteously gave me the route. I thanked him with effusion, and most probably should have found his directions of infinite value had he but delivered them in English instead of Dutch. As it was, I put myself into a London-looking cab (the driver very properly wore a military cockade), and was soon at one of the best hostelries in Holland. Situation pleasant—of course overlooking a canal—rooms comfortable, kitchen all that could be desired.

And now what did I do in Amsterdam? Why, I went to the Exhibition. And what was it like? Well, a Dutch edition of those that had gone before. At the Naval display before the Royal Hospital at Chelsea, there was a model of the Victory, with a representation in wax of the Death of Nelson. At Amsterdam there is a model of a mail-boat, with a representation (in breathing humanity) of people drinking beer.

At Paris there was a Tour Eiffel, with a magnificent view at the summit; at Amsterdam there is a tower in the shape of a colossal elephant, with a fine display on every floor of beer. At South Kensington there was a realistic reproduction of Old London on temperance principles. At Amsterdam there is a realistic reproduction of Old Holland served with beer. Go where I would I ran across beer. The grounds of the Exhibition were dotted with booths. Before many of them were very decent orchestras discoursing sweet music. But the foreigners were there not only to attend to the music, but to drink beer. The Exhibition proper (contents small and select, with few English exhibits) was not apparently much of an attraction. I readily understood the reason—it was not devoted exclusively to beer. In what I may term the Exhibition annex I found any number of specimens of the oriental merchants in the fezes, who were wont in the olden days to enhance the joys of Olympia and Earl's Court.

"Come here, gentlemans," cried half a dozen in a breath, "I will sell you this!"

But they didn't. Having done the exhibition and the admirable museum, with its wonderful armour and marvellous old masters, I sampled a music hall. I went to "the Crystal Palace" (vide guide-books), a magnificent building, that no doubt had been built with the highest aspirations and had come in the progress of time to the loftiest tumblings. A portion of this noble institution had been converted into a place of entertainment. Small stage with miniature scenery, trapeze, orchestra. Audience almost entirely Dutch, entertainment almost entirely English. Several British singers. One, a gentleman in evening dress covered by a long Newmarket overcoat, with a répertoire redolent of Holborn and the Surrey side, sang about "Nine in a row" who (so I understood him to assert) "rolled down the street" when (if I am not mistaken) they were rather "rocky about their feet." Then he had another ditty which referred to his want of value. Was he worth anything? He appealed to the Dutch audience. Some of them (possibly friends of the singer) replied in the negative. Then he expressed his conviction that he ought to be chucked out. The spectators cheered, and seemed well satisfied with the programme. Whether they were able to appreciate all the topical allusions is open to doubt, but I am certain that they were thoroughly enjoying their beer.

I went to the market. An enormous crowd surrounded one booth. The salesman was singing a song in honour of his wares, which were composed of pieces of broken iron! So far as I could understand the manners and customs of the vendors, the golden rule seemed to be amongst them, "When in doubt take off the door to the outhouse with the three broken panes of glass, the back parlour chandelier that lacks a chain, and the disused baby's cradle, and sell 'em all by auction."

I looked in, of course, at the Cathedral. My guide could not speak French, but he understood English. He showed me the tombs of several admirals.

"Where is Van Tromp?" I asked, taking an interest in the career of about the only Dutchman whose name I know intimately. Then, to make it plainer, I added, "Whar is das Van Tromp?"

My guide turned up his nose contemptuously, and said something (so far as I could comprehend him) about Van Tromp being in "de odder kirsher." Later on, when I asked the use of a sort of vestry, he murmured something about "Balaclava." From this I took it that he could not make himself understood. But I was wrong. I did not know much about the Dutch coinage. When I bought anything I invariably kept my hand waiting for change until the supply was exhausted. Sometimes I put forth my hand a second time with the result of getting a few extra coins. There are guilders, little pieces that look like a doll's silver pennies, and a showy coin that suggests a sixpence in a decline. These latter are worth, I fancy, about three halfpence a dozen. I gave the cathedral custodian one of these sixpences in a decline. But it was not enough, not nearly enough, so I exchanged it for a doll's silver penny, when he beamed with gratitude.

Would that I could tell of the other attractions of Amsterdam, of the Royal Palace, the Zoo, the theatres, and the canals. But exigencies of time and space say "No." Those who want to see and hear have only one thing to do. Let them hie to the Hook of Holland, ho, to the Dutch capital, and further description will be unnecessary.

During a severe thunderstorm at Bjelina, in Bosnia, according to the Pall Mall Gazette's "Science Notes," there fell a remarkable "shower of whitebait." This phenomenon has been easily eclipsed at London, in England, where it recently rained cats and dogs.

["Blackberry or strawberry juice rubbed slightly on the cheeks, and then washed off with milk gives a beautiful tint. The garden-beet is also an excellent cosmetic: the beet is cut and the juice applied gently with a camel's hair brush."—Announcement quoted by Mr. James Payn in "Our Note Book," "Illustrated News."]

Alas for the bard's and the ingénue's dream!—

Even Nature, it seems, joins Art's plot to betray us.

We've heard cheeks compared to strawberries and cream,

But that earth's sweetest fruit such a false trick should play us,

In conspiracy base with fresh milk from the cow,

Brings the red flush of wrath to the snowiest brow.

What, sweet Mother Nature lend aid to a cheat,

And play Madame Rachel in faking complexions!

Arcadia's vanished, naught's native or sweet,

The daintiest Beauty wakes doubtful reflections,

When for ought we can tell her ingenuous blush

Is—a compound of beet and a camel's-hair brush!

It is a great thing to know—and one must believe it if one believes, as I do, in what the newspapers say—that every single male member of the upper or fashionable ranks of society is at this moment engaged in slaughtering grouse. It is of course well known that every member of Parliament is, on his election, presented by a grateful country with a large and well-stocked grouse-moor, situated in one of the most picturesque and romantic parts of Scotland, and no one (not even a brewer) is ever raised to the peerage unless he can prove that at least three generations of his family have shot grouse regularly on the 12th of August on a moor of their own. Thus is the connection of both branches of our legislature with sport safeguarded.

Whenever the 12th of August, or, for the

matter of that, the 1st of September or the 1st of

October, comes round with the revolving year, we

are informed in every newspaper that "Sportsmen

were early astir." There is about these words a

halo of tradition so ancient and venerable as to

have become almost sacred. Imagination conjures

up the picture of happy bands of shooters all duly

booted, gaitered, gunned, cartridged and cigarred,

sallying forth with dogs and keepers at 5 A.M., no

doubt after eating, as condemned men do, a hearty

breakfast. Of course this may be so. I have read

it so often that I hardly dare to doubt it. My own

experience, however, is that sportsmen are not

specially early even on the 12th, although keepers

and other professional guns who cater for the

London market are often so early as to anticipate by more than a

few hours the recurring anniversary.

Now with black London's close and torrid street

Stern Caledonia's heathered moors compete.

Lo, well equipped with cartridge-bag and gun,

Concurrent streams of rank and fashion run

Where, though the birds be strong upon the wing,

Not unrewarded sounds the frequent ping;

Where dealing fate to feather (and to fur)

The early sportsman is perceived astir,

And in the lengthy language of the chase,

A bird's no bird, but merely half a brace.

Some skilful, some not fit to shoot for nuts,

Walk for their game or take their stand in butts;

And, wondrous fact, as all the scribes proclaim,

Each from a separate butt destroys his game.

At least it was so when the Emperor shot, so

With non-Imperials it perhaps is not so.

I am never irritable myself; I am sometimes justifiably annoyed by the unreasonable conduct of a friend. But I have often noticed the most melancholy irritability in others, and have wondered why they gave way to it, and what it portended. Now I know. I have been reading the Medical Press and Courier, and I learn from it that "this hyperæsthesia of the temper is the direct outcome of overwork and want of sleep; in fact, it is a morbid sensitiveness of the cells of the cerebral cortex due to exhaustion or under-nutrition. Irritability is, therefore a clinical sign of some importance, the more so because it is often the premonitory indication of impending breakdown. Under these circumstances, the condition is usually most marked during the forenoon, and is associated with a distaste for food at breakfast time. Later on, even the humanising effect of a good lunch fails to raise circulatory activity to the standard required for adequate cerebral nutrition, and the irritability becomes chronic, yielding only to the influence of repeated doses of a diffusible stimulant, such as brandy and soda. The remedy naturally only aggravates the symptom, which is sooner or later followed by other manifestations of cerebral exhaustion."

When you're lost in the whirl of a medical vortex,

You gasp and you grasp, and you'll struggle in vain;

For it seems you have cells in your cerebral cortex,

Which is somehow connected, I fancy, with brain.

Exhausted and panting with under-nutrition,

You dare not presume to declare yourself well,

And you rapidly tend to complete inanition,

Produced by a morbidly sensitive cell.

The result is a wound to the temper, a something

Not as deep as a well, but, no matter, it serves,

Perplexing your friends, who pronounce it a rum thing

That Dick—that's yourself—should have gone in the nerves.

You toy with your breakfast; the kidney, the kipper,

The egg that is buttered, the egg that is fried,

The tea that once found you a regular sipper,

Unsipped and untasted you push them aside.

Your lunch of cold beef with the gaff and the shandy,

You simply can't face it, your head is one ache:

A "diffusible stimulant" (alias brandy)

Is all that you wish for and all that you take.

A day or two back all your manners were courtly,

Alas, what a change is apparent to-day,

For you jump on your friends, and you take them up shortly,

With a quarrel a minute whatever they say.

Then, in spite of the canon that's set 'gainst self-slaughter

(In the language of verdicts it's felo de se,)

Some day you'll be found with your head in the water,

Six inches will do, or attached to a tree.

There have been some difficulties at Brierly Hill. At a recent meeting of the Urban Council a letter was read from the Local Government Board asking for information with regard to a communication which Dr. Ellis, the medical officer of health, had addressed to them. This referred to the fact that Dr. Ellis had ordered a "dumb" well at the Town Hall to be cleared out. What is the use of a dumb well? Even if it contains the truth it cannot speak it. Personally, I prefer a babbling brook.

What is this? Is it a revolution or merely a mistake? Do I sleep, do I dream, or is visions about? These questions occur to me on reading that at Ironbridge the other day a clown, a member of a circus, was brought up on remand charged with stealing £1 10s. and several articles, the property of his landlady. And he was actually sentenced to fourteen days' hard labour. All I can say is that I have rarely allowed a year to pass without seeing at least one clown steal a string of sausages, a lady's bonnet, two plump babies, half a dozen fowls, the greater part of a general dealer's property, and the upper half of a policeman. Nobody bothered him about it. In fact, everybody expected him to do it, and there would have been great dissatisfaction if he had observed the laws against larceny. And yet when a clown at Ironbridge acts as clowns are intended to act, an unfeeling bench visits him with a fortnight of hard labour. This is preposterous. There ought to be an Amalgamated Union of Clowns to protect its members from such an outrage.

Those who study the reports of meetings of Town Councils learn many things. For instance, at Bristol the other day, during a discussion of passenger tolls at the docks, Mr. Gore complained that they had been hocussed by the chairman of the sub-committee that day. Mr. Baker objected to the word "hocussed" being applied to him, but added that they had been hocussed out of a good deal of time to-day, and Mr. Gore retorted that they were going to be hocussed out of another quarter-of-an-hour yet. Mr. Baker asked Mr. Gore to withdraw the word, and Mr. Gore refused. Matters had apparently come to a desperate pass, when it occurred to the Mayor to inquire what the word "hocussed" meant. Mr. Baker thought it was something akin to cheating, whereupon Mr. Gore, in the handsomest manner, said that knowing the meaning of the word he would now withdraw it. The only thing that was not explained was why Mr. Gore had used a word of the meaning of which he was ignorant. There is a fatal attraction about the sound of certain words which forces speakers to use them entirely without regard to their actual meaning.

Laura (to her rich Sister, who has been extravagant as usual). "I do think it's a mistake to buy an Ugly Thing one doesn't want, merely because it's dear!"

(A Rejoinder to "Harry on 'Arry.")

Dear Charlie,—My eye and a bandbox! Wot next, and wot next, and WOT next?

'Ere's a Harry 'as mounted the pulpit, and taken poor me as 'is text!*

'E bangs Boernerges to bittocks, this lar-de-dar bagman—in silk—

And 'e's going to do me a fair knock-out as sure as a whale ain't a whilk.

I larf, I do, Charlie, tremenjus! Wot's needled my nabs, it appears,

Is 'is being mistooken for Me!!! Well, 'e needn't 'ave no blooming fears!

The public ain't all of 'em mugginses, some of 'em can twig a joke.

Confound 'im with me? Yus, they will—when they can't tell Bend Or from a moke.

'E calls me,—yus, me,—"the cad-cockney well known to the 'Eath and the 'Arp."

Well, that's a fair challenge, old man, and I mean being on to 'im—sharp!

I'll take 'im—with 'is aitches chucked in—with one 'and whensomever 'e likes;

And "Cads" do the road in smart dog-carts as well as afoot or on bikes.

"'Arry the Cad!" Great Jemimer! Jest fancy our Harry's disgust

At the thought of their knocking 'is aitch out! 'E's fair on the bile and the bust.

Way oh, Harry! Do keep yer 'air on, old pal, if you've got any thatch,—

For it's wonderful 'ow these swell Harries go in for the shiny pink patch!

It's their brines working through—or their bumptiousness. I've got no hend of a crop,

As looks, when I've 'ad a close clip, like a fuzz-bush a sprouting up top;

But lor! these 'ere munchy-mouthed mashers—with aitches—as gives theirselves hairs,

Carn't grow any, not arter thirty, the bladder-o'-lardy-dar scares!

'Owsomever, that ain't to the pint, Charlie. Wot is a Gent? That's the nip!

Well, it's partly a matter of "snap"-like, and partly a matter of "snip."

If I've got the grit and the gumption, and know 'ow to tog like a toff,

I've got the true gent in my nyture, and them as ain't got it—they're hoff!

But "aitches" won't do it, my pippin! Yer grammar may be quite O K,

All yer parts o' speech proper as pie, and yer spellin' fust chop in its way,

But if you can't rattle and patter, and 'old up your end like a man,

All yer mincey-wince mealy-mouthed has-p'rates is nothink but slop and cold-scran.

You may garsp out yer aitches in spassums, until you 'ave got a sore throat,

And it won't give you "clarss" arf as much as cool cheek and the cut o' your coat.

Wot the mivvies call hinsolent hotoor, wot cocktails dub cocksure conceit,

With snideness and "suitings" to match,—that, dear boy, is wot makes the eleet.

There, Harry, you've got it in once! And, now, dear boy, 'ow about you?

Well, I guess, as the Yankees observe, you 'ave bit hoff a chunk you can't chew.

Bit vulgar? Well, never mind that, mate, for, spite of your finnickle fuss,

It's jest wot you guffins calls "vulgar" as swells love to borrer from hus.

There's chick in it, Harry, and that's wot you chalk-witted chowders ain't got.

Not one snappy snide phrase in your sermon, except that old gag "tommy rot,"

Which you didn't invent, nor your sort; it's hus aitchless ones start all the fun,

And our yesterday's wheeze you freeze on to to-morrer, as sure as a gun.

And the same with your sentiments, Harry. Your loud "Rule, Britannyer" sall right;

But we gave you the patriot tip, years ago, in "We don't want to fight."

You water it down, and then wave it as if 'twos your own privit flag,

And then, arter nicking our principerles, slang us—and with our own gag!

I'm one with you as to the furriner, leastways you seem one with me,

And when you rile up at the rot about "'Arries Abroad," I agree.

I shan't discumfuddle myself if they don't like my tystes or my togs.

Let the Germans go 'ome and eat coke, Frenchies stick to their snyles and stewed frogs.

But when you suggest as the "aitch" makes a 'a'porth o' difference—Bosh!

You call me a "aitch-droppin' howler," whilst you are "a gent"! It won't wash.

Me a Rad,—arter all I 'ave written? 'Taint much on it you can 'ave seen.

And to ask Punch to give me the chuck!—yah! it's mean, Mister Harry, it's mean!

* See "Harry on 'Arry," p. 81.

Lord S-l-sb-ry (Skipper). "WELL, ARTHUR, WE'VE WON OUR RACES—AND NOW WE CAN TAKE IT EASY!"

["I hope we shall have a period of calm and peace."—Mr. Balfour's Speech, August 12.]

"A Battersea bounder," too! Rats!!! Do you think I'm a pal o' Jack Burns?

Mix me with "the masses"? Great Scott! It's a thought as the soul o' me spurns.

You jumped-up, cheap, Coventry bagman, silk-sampling, no doubt, is your biz,

But sampling "the classes and masses" is not, blow me tight if it is!

Yah! Pack up your ribbings, and aitches, and don't aggranoy me no more,

But jest mind your own interference! A bounder you are—and a bore.

You've borrered my patriot sperrit, you've borrered a slang phrase or so,

But there's one thing, my boy, you carn't borrer, and that is my rattle and go!

There, Charlie, I've given 'im beans, this 'ere Harry, as carn't abear Cads,

And wants to put up a aitch-fence like to keep out us row-de-dow lads.

Let 'im call 'isself 'Enery at once, that's the badge for sech bounders to carry,

And then 'e may bet 'is larst bob as 'e won't be confounded with 'Arry.

[A correspondent, writing (to the Daily Chronicle) from Harwich, describes the deplorable condition of work prevailing among the shrimp catchers. "These poor fellows," he says, "are at sea twelve hours a day catching, and have to devote four hours more to boiling and packing for London. And yet all the middlemen send them down is from fourpence to fivepence a gallon."]

Toiling sixteen hours a day, and for precious little pay,

Seems a blend of prison labour and starvation,

Yet I do hear some suggestion that the "burning Labour Question"

Is the one that mainly agitates the nation!

No Trades Unions have we, and I do not rightly see

How "Co-operative Wholesales" help our like,

Who must slave in sun or shine, cramped and chilled in the salt brine,

With the choice of sheer starvation if we "strike."

Labour Questions? Well, here's one. When the I. L. P.'s have done

A-wrangling and a-jangling o' th' Election;

When Mister Chamberlain has done counting o' the slain,

And Keir Hardie a-explaining his rejection;

When Tillett and John Burns have both taken of their turns

At wildly lamming into one another,

It might help to "cool their parritch" if they cast a glance at Harwich,

And the state o' their poor shrimping "man and brother."

Ah! above our nets to stoop, and to scrape, and scratch, and scoop,

In loneliness laborious and risky,

Is not a task, in truth, to encourage sturdy youth,

Or make work-worn old age alert and frisky,

Then with sore and aching back we have got to boil and pack;

And then the hungry middleman's remittance,

When it comes, is precious small, what a docker-lad would call

A paltry and a belly-pinching pittance.

Yet the Fish-Rings, they do say, are quite prosperous and gay,

And Billingsgate is wealthy; and the skimpers

Who so cut our profits down, live like fighting-cocks in town,

On the ill-paid toil of fishermen and shrimpers!

Ah! That "Harvest of the Sea" is a sounding phrase, but we

Find such "poetry" for us has little meaning.

The "Fish-Farmers" may do well, as their profits plump and swell,

But, alas! for those who have to do the gleaning!

Projected Re-visitation—Ilfracombe—Torrs Walks—En route—Start—In Dock—Out—Tender Thoughts—On Board—Reception—Greetings—Exciting Search—Parting—Off!

Happy Thought.—Revisit Ilfracombe. Hire highest possible house at the lowest possible price close to celebrated "Torrs Walks." Why called "Torrs Walks"? Probably original Torrs who discovered Ilfracombe used to walk here; one stormy night Torrs lost his head and legs; then fell from sheer height of several hundred feet into boiling sea; boiling sea made it hot for the unhappy Torrs; Torrs only walking, not swimming. Therefore end of Torrs. Family name perpetuated in Walks. Years ago, price to ascend Torrs was one penny per head, body included. Tariff gone up since then. To Torrs Torr-tuous Turnings admission Twopence. Extra penny might have improved paths. Here there is as much "winding up" as in bankruptcy. "Excelsior" is motto of visitor; likewise of proprietor who put on the extra penny. No matter; not another spot in England where pedestrian can get better air, better exercise, and finer views, all for twopence!

Friendly Advice—gratis.—Always carry waterproof. If practicable get someone to carry it for you. Never know when you may want it, or when you mayn't. Stop for five o'clock tea on Torrs top. Whistle merrily "Torr-eador contento" as you descend, and you will be giving one of the best airs in Carmen in return for about the finest air in Devonshire.

How to get to Ilfracombe.—Per rail, London and South-Western. Picturesque line of country. Another, and a longer route, per mare et terram, and therefore more varied and health-refreshing, which are important points to score if your holiday be circumscribed, is to take passage on board steamer, Pacific Orient Line for choice, which stops at Plymouth en route to give a last glance at Old England before proceeding across the Bay of Biscay to Naples, and, ultimately, Australia. Only drawback to this is the start from Fenchurch Street. Fenchurch Street Station enough to make anyone start. Wanted here a spacious, light and airy place where passengers carrying "hand properties" can move about rapidly without loss of that equanimity of temper which every traveller should cultivate under circumstances that would try even the joviality of that utterly impossible creation Mark Tapley. Still Mark Tapley is an ideal to be lived up to as near as may be; and the passenger who, with bag in hand, while struggling with mixed crowd in Fenchurch Street Station on the departure of any important Tilbury Dock train, can be jovial or even ordinarily polite, is already in a fair way towards earning the Ideal Tapley Medal.

Tilbury Wharf. "And at this wharf of Tilbury" why not more porters? Why not a covering to the landing-stage, where at present, the traveller, like the sky parlour in ancient song, "exposed to the wind and the rain," will be thoroughly drenched while awaiting the advent of the tender. Happy Thought.—To-day, fortunately, fine.

These queries occur to me as I stand on this floating quay, and witness in the distance the "tender parting." There will be many "a tender parting" beside this one to be seen when the Orotava gets her steam up, and quits Tilbury for Melbourne.

We board the Orotava, which is to board and lodge so many of them (with another contingent going overland, and joining the ship later on) for the next month or so.

I am personally introduced to the captain by some kindly friends who come to see me off, and whom, as I lose sight of them in the crowd, it is soon my turn to "see off"; as subsequently I can only catch a glimpse of them in the crowd, on the tender, as they depart for shore, when we wave hands to one another implying thereby all sorts of good wishes. After making the captain's acquaintance, I am introduced by some light-hearted companion—everyone on board is either boisterously gay or in the deepest grief—to a good-humoured-looking portly gentleman, whom, there being nothing whatever nautical in his appearance, I should have taken for a landed proprietor, "one of the olden time," had I not very soon discovered him to be something uncommonly superior in the Nautical Pacific Service, and the friend in need, without whom no passenger's happiness is complete, that is, speaking from practical experience, if the destination of that passenger is only Plymouth, as was mine.

Farewell! The tender is about to depart. It seems to me to be as full as when it arrived. "Cheers, tears and laughter:" only the laughter is a bit forced, while the tears are natural, and the cheers most hearty. The tender hesitates. Tug evidently tender-hearted; can't bear to part with the good ship Orotava. No; this is not the cause of the delay. Some one is waited for. Tender crew impatient. Where is he? Who is he? Find him. Some one, in ordinary frock coat and top hat but clearly an official on board tender, puts both hands to his month and shouts out what sounds to me like "Wait for Mister Tubbs!" Evidently tender cannot go ashore without Tubbs; equally evident that Tubbs is not to sail with the Orotava. Puzzle, to find Tubbs. Stewards, chief officers, mates, men rush in all directions to rout out Tubbs. Look-out man aloft in sort of suspended clothes basket cannot get a sight of Tubbs either in the offing or out of it. Nothing like Tubbs to be seen anywhere. Somebody reports at top of voice "He's with the captain." Captain up above somewhere, invisible, denies soft impeachment as to being cognisant of the whereabouts of Tubbs. What is Tubbs doing? Playing hide and seek? Search light turned on into darkest and deepest depths of Orotava. No Tubbs. Suddenly first gangway withdrawn, and grasp of tender partially relaxed. Exciting moment. Crew of tender rattle second gangway threateningly: their patience is almost exhausted. The cry goes up once more for Tubbs ahoy! Even the weeping wives and sorrowing friends, lovers and children forget their dear ones for a moment and strain their eyes in every direction, gasping for a glimpse of invisible Tubbs. At last a small, stoutish figure appears on the gangway. Is he hatless? breathless? Not a bit of it. He walks the gangway as if he yet had hours of leisure before him, and was quite unconscious of having kept anyone waiting. It is Tubbs himself. The self-possession of Tubbs is remarkable, nay admirable. He notices nobody. Speaks to nobody. Suddenly he disappears; the gangway is withdrawn; more cheers, more waving of pocket-handkerchiefs, and the tender, with the impassive Tubbs to boot, drifts out of sight, and the Orotava is fairly under weigh.

Ugly Man (who thinks he's a privileged wag, to Artist). "Now, Mr. Daubigny, draw me."

Artist (who doesn't like being called Daubigny, and whose real name is Smith). "Certainly. But you won't be offended if it's like you. Eh?"

Moore hymned the "Irish Melodies,"

And as he harped all heeded his chords.

But heaven help the bard who tries

To harmonise the "Irish Discords"

The Paddies quarrel, gird, and carp,

Blend petty squeak with mad mock-thunder.

No Minstrel Boy may tune that Harp

Since faction "tore its chords asunder."

A wedding of great interest to Welsh society, which took place lately in the Rhondda Valley, was that between Mr. Smith and Miss Margaret Abraham, daughter of "Mabon," M.P. Of course "Ma bon-nie bride." The presents, though numerous and handsome enough, did not somehow include one that, having in view the nationality of the interesting pair, would have been singularly appropriate. There was no gift of Taff-eta.

(A Caution to those who are Interviewed.)

The celebrity awaited his interviewer with some impatience. He had arranged his story with considerable care. He was prepared to show that he was the best of boys at school, the most studious of students at the university, the worthiest of men at all times. He felt sure that when the record of his life was published, preparations would be made to erect a statue and a glass window in his honour. And so he was satisfied.

In due course the interviewer appeared. The man was bland and persuasive. He requested the celebrity to take a chair, and then placed his hand upon his brow. The celebrity gazed into the eyes of his visitor with a lack lustre stare, and then seemingly sank into a heavy sleep.

"And now I am prepared to begin," murmured the interviewer, taking out his notebook. "My worthy Sir, I command you to tell me all. Mark you well—all." And then the celebrity, in a monotonous tone, revealed the secrets of the past.

The celebrity was furious. The interview had appeared, and was far too true in the story of its subject's life to be pleasant. There was no assertion that the celebrity had been the best of boys at school, the most studious of students at the university, the worthiest of men at all times. On the contrary, the celebrity had "come out" in rather unflattering colours. So that eminent man was simply furious. He had sent for his interviewer, and awaited once more his arrival with impatience. In due course his biographer turned up.

"And now, Sir," said the celebrity, in tones trembling with anger, "what do you mean by suggesting that I tried as a child to slaughter my maiden aunt?"

"Did you?" was the calm rejoinder.

"That is beside the question. And why did you assert that I had told you that I never did a day's work at the university?"

"But you did say so—didn't you?"

"Again beside the question. And what did you mean by stating that I had deserted my wife, and turned my children out-of-doors at a moment's notice?"

"But were those statements true or untrue?"

"That you have not received a writ for libel is my answer. But how came you to know these unpleasant details—who told you?"

"You did."

"I did! When, where and how?"

"When I saw you here, and at my request."

"I do not understand you," murmured the puzzled celebrity. "Why should I tell you all this?"

Then came the explanation.

"You told me all I wanted," replied the interviewer, "because I am a hypnotist?"

"Indeed!" returned the celebrity when he had recovered from his astonishment; and then, after a moment of deep consideration, he gave his visitor the names and addresses of the more hated of his rivals.

Some advance on Peace's journey

We may reckon. War's disasters

Won't attend this great Chess Tourney.

And the Meeting of the Masters.

Steinitz, Lasker, Tschigorin,

Blackburne, Bird, or any other,

Whichsoever champion win,

Will be hailed as friend and brother.

Senlac saw another sight

When the Norman whipped the Saxon.

This serene and bloodless fight

Skill and patience lay sole tax on.

Here no arrow ends the fray,

(Though a narrow victory may do,)

Whereat Punch must shout hooray!

Play on, great Chess Masters, pray do!

May the best man meet success!

(Big guns have had pretty bastings!)

And no Battles, save at Chess,

Ever stain our English Hastings!

(At Swearing-in Time for the new M.P.'s).

The cry is still they come—the new M.P.'s!

The difference 'twixt them and us, no doubt,

Seems but one letter, but how vast it is!—

They are "sworn in," but we are just worn out!

Nervous Traveller. "Hi, Man, steady! Don't drive so fast!"

Hibernian Driver. "Sure, yer Honner, an' I'm only thryin' to make the ould Mare forget how often she has been on her Nose at this blissed Hill!"

EXTRACTED FROM THE DIARY OF TOBY, M.P.

House of Commons, Monday, August 12.—"Are you ready? Go!" No mistaking the voice. It was the clear, sharp notes of Hemprer Joe, ringing from behind Speaker's Chair, high above buzz of talk and bustle of movement in crowded House. Wondering what it might portend, when discovered Prince Arthur and Squire of Malwood entering simultaneously, after the fashion of the Bounding Brothers from the Breathless Baltic. Only, if you remember, those eminent artistes appeared in ring from directly opposite approaches, advancing towards each other with startling, though graceful evolutions. Prince and Squire, on contrary, started from door at back of Speaker's Chair, advanced fair toe and heel to table; walked step by step together along either front bench, till each reached the seat kept vacant for him.

House so surprised at this performance it almost forgot to shout. What usually happens on like occasions is for one Leader of Party to take his seat amid loud cheers from his friends, taken up with strident voice from other side when their man comes in. Now cheers, if indulged in, would mingle, and might be misunderstood. A welcome meant for Prince Arthur might seem to be bestowed upon Squire, and vice versâ, as Mr. Anstey once said. Whilst perturbed House looked on, Hemprer Joe, having watched his men, fairly started, reach their goal, followed with swinging step and the inevitable orchid.

To see him seat himself on Treasury Bench, the right-hand man of a Tory Government, too much for the feelings of Tim Healy, usually held in stern reserve. During interval of General Election Tim been holding sweet converse with his colleagues in general, Blake and Tay Pay in particular. By odd chance he, taking his place in new Parliament to-day, found himself seated between his two friends, to whom presently entered the "dear Justin" of a voluminous missive. Soothed by such companionship Tim in melting mood. But sight of Hemprer Joe finally crossing the gangway, formally completing marvellous journey from Birmingham to Hatfield, too much for trained equanimity. Tim groaned aloud. Swift MacNeill roared as if in anguish. Dr. Tanner (figuratively of course) cut himself with knives, emitting sounds that nearly frightened to death two new members seated on either side of him. l'Hemprer smiled benignly. Clerk at Table, dexterously interposing, pointed spectral forefinger at John Mowbray, who rose to "move that the Right Hon. William Court Gully do take the Chair as Speaker."

A delicate task, seeing that a few short months back he had run White Ridley for the Chair against the man whose price to-day he fixed far above rubies. Admirably performed; made easier by fact that meanwhile Gully had filled the Chair, acquitting himself in manner that justified choice of friends and extorted admiration on other side.

"All very well," says Sark, "to talk about preserving cherished traditions and best precedents of House. But suppose Gully had been—I won't say a failure, but—anything short of perfect manner in the Chair, where would he have been to-day?"

Certainly not in the Chair, whither Mowbray led him, escorted by John Ellis, and where Prince Arthur welcomed him in terms which indicated that now was the dearest desire of his heart fulfilled. As for Squire of Malwood, he was so affected that he fell into his most funereal manner.

"One would think," said Chaplin, himself in the highest spirits, "that he had come to bury Gully, not to praise him."

Business done.—Speaker re-elected.

Tuesday.—"Our army may have sworn terribly in Flanders," said Mr. Milman, tossing back the wig from his throbbing brow and rearranging his crumpled gown; "it was nothing to what the House of Commons can do when called upon."

Four o'clock now. House met at noon, and ever since they've been swearing away. Prince Arthur and Squire of Malwood led off, in company with Hicks-Beach, Goschen and Henry Fowler. He no longer the Great Mogul. Has folded up his turban, put away [pg 96] his kaftan, hung up his yataghan, and once more resumed the dress of commonplace Englishman. House loses something of its picturesqueness. But, Fowler says, change of estate has some compensations. At least now he has not to receive the Shahzada in his family circle, handing him round tea and cakes, and attempting to converse with him in the Afghan tongue, imperfectly acquired by study of Ollendorf. Sense of renewed freedom made Ex-Secretary for India throw added fervour into his bout of swearing.

The Elect of Whitehaven!

A-g-st-s H-ld-r, Esq., M.P. "Well really, now they come to mention it, the likeness between myself and Sir William Harcourt is very remarkable indeed!"

A little excitement at first in crowded House. No reason why Members should insist on being sworn-in right away. Might look in later in afternoon, when pressure was over; or call to-morrow; or stroll in all by themselves on Thursday or Friday. Human instinct irrepressible even in Members of Parliament. Must be in the first flight, whatever is going on. So swarmed round table, made dashes for stray copies of the New Testament, snatched at slices of cardboard containing form of oath, as the anonymous drowning man clutched at the fortuitous straw. Milman, standing at table, administering oath, had a hot time of it for an hour. Thereafter excitement began to tone down, and just now flickered out.

Business done.—Swearing in Members.

Thursday.—"Accidental relations in directorial capacity with a great railway corporation have," said David Plunket, "brought to my knowledge the fact that when signals on the line show a green light, caution is necessary. This afternoon, when I observed Tanner come in with flaming green necktie I feared the worst."

The worst didn't befall till midnight approached. But things in immediate neighbourhood of Tanner been seething for some time. His topographical position a little trying. Faced by triumphant majority of anti-Home-Rulers, distinctly seeing on Treasury Bench two Balfours where formerly only one had sat, he was irritated by having on his flank the Redmond frères, Harrington, Clancy and other compatriots almost worse than Saxons, not to mention the pain to a man of peace of consciousness that between his friends and colleagues Tim Healy and John Dillon there was something lacking in the way of perfect loving-kindness. Then there was Boanerges Russell on the Treasury Bench. Bad enough to have had him sitting on corner of top bench immediately opposite. To see him curling up his legs on Treasury Bench, one of Her Majesty's Ministers, drawing a salary quarterly with regulation and despatch, was more than a humble but patriotic medical practitioner could stand. "T. W. Russell!" cried Tanner, with fine irony, and bold disregard of Parliamentary usage, which forbids mention of Members by name. The observation was by way of postscript to inquiry as to whether the Government really intend to try and prevent the murder of any more missionaries in China, and bring in an Irish Land Bill?

A Piece of Crown-Derby Ware!

Design for Bemrose-and-Drage Ornament for the Chimney-piece. No publican's parlour should be without this charming memento of a great victory.

No satisfaction forthcoming on these points. Tanner sat and brooded by the hour over fresh wrongs of Ireland, complicated by these proceedings in China. It was Harrington who accidentally and unintentionally dropped the spark which, as a Member once observed, let slip the dogs of war. "That's a lie!" remarked Tanner, by way of criticising one of Harrington's statements. Remark made in quite ordinary way; just as if he had been moved to say "How d' you do?" or, "It's a fine day." Friends and countrymen sitting near not in slightest degree disturbed. Only Tanner's way. Harrington, in fact, had commenced next sentence, when voice of long-suffering Speaker heard, inquiring whether he had heard aright, one Member accusing another of being a liar?

Tanner a little flustered at this extraordinary and unexpected punctilio. If objection taken had not been so sudden, the Doctor, most amiable and good-natured of men, who wouldn't hurt a fly much less flout a Speaker, would have apologised. But House angrily roared; Speaker remained standing; Hemprer Joe, leading House in temporary absence of Prince Arthur, appeared on scene with bit of paper he had in his pocket, containing, by rare chance, written formula for moving suspension of disorderly Member. So Tanner was "named," and presently escorted from House by Deputy-Sergeant-at-Arms, shaking his fist at unoffending Secretary for the Colonies, shouting "Judas! Judas!" at top of strident voice, probably restrained only by general hurry of proceedings from demonstrating how L'Hemprer was at bottom of the murder of missionaries in China.

Business done.—Address moved. So was Tanner—out of House. Robertson, M.P. for South Hackney, delightful in seconding Address. Confided to House that he was first genuine East-Ender ever placed in such position.

As he was. The Seconder of the Address. As he ought to have been.

"Hon. Members would probably be interested in seeing what a dweller in the East End was really like, especially when he was to be in some costume suitable to the occasion."

Friday.—Unprecedented scene to-night. Attorney-General for Ireland, rising from Treasury Bench, opposed John Dillon's amendment to Address; Solicitor-General for Ireland, springing up from Front Opposition Bench, warmly supported it. Both maiden speeches; manner distinctly different. Atkinson prim, severe, official; Hemphill friendly, genial, richly eloquent.

"I fancy," said Prince Arthur, with one of his sweet smiles, "our Solicitor-General has studied his Parliamentary manner by observing the graces of a popular conductor on taking his seat in the orchestra." Business done.—Still debating Address.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol.

109, August 24, 1895, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 46895-h.htm or 46895-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/4/6/8/9/46895/

Produced by Malcolm Farmer, Lesley Halamek and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by

freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm works in compliance with the terms of

this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with

the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by

keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project

Gutenberg-tm License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in

a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check

the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement

before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or

creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project

Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning

the copyright status of any work in any country outside the United

States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate

access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear prominently

whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work on which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed,

copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is derived

from the public domain (does not contain a notice indicating that it is

posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied

and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees

or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work

with the phrase "Project Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the

work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1

through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the

Project Gutenberg-tm trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or

1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional

terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked

to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works posted with the

permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any

word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or

distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format other than

"Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official version

posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site (www.gutenberg.org),

you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a

copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon

request, of the work in its original "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other

form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works provided

that

- You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is

owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he

has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the

Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments

must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you

prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax

returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and

sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the

address specified in Section 4, "Information about donations to

the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation."

- You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or

destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium

and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of

Project Gutenberg-tm works.

- You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any

money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days

of receipt of the work.

- You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set

forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from

both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and Michael

Hart, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark. Contact the

Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

public domain works in creating the Project Gutenberg-tm

collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain

"Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or

corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual

property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other medium, a

computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by

your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with

your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with

the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a

refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity

providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to

receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy

is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further

opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO OTHER

WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO

WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages.

If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the

law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be

interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by

the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any

provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in accordance

with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production,

promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works,

harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees,

that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do

or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg-tm

work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any

Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers

including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists

because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from

people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future generations.

To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4

and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive

Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent

permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is located at 4557 Melan Dr. S.

Fairbanks, AK, 99712., but its volunteers and employees are scattered

throughout numerous locations. Its business office is located at 809

North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email

contact links and up to date contact information can be found at the

Foundation's web site and official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To

SEND DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any

particular state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations.

To donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project Gutenberg-tm

concept of a library of electronic works that could be freely shared